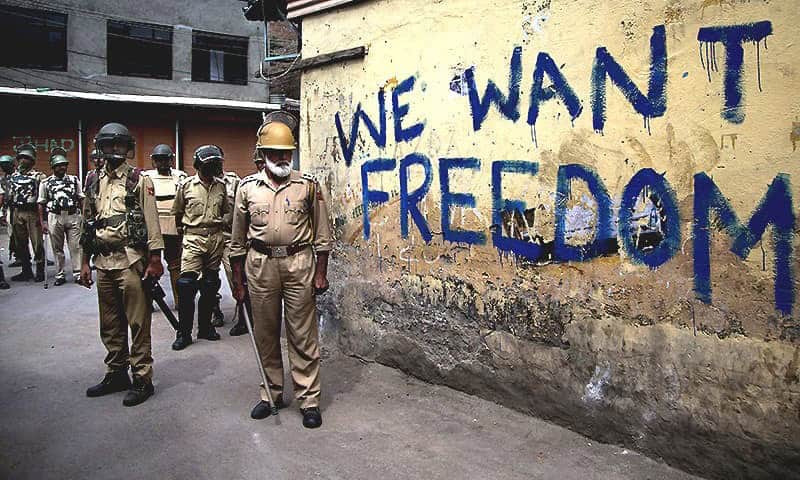

In the age of Pax Romana, a mere incantation of the magic phrase “Civis Romanus Sum- I Am a Roman Citizen” would entail the complete protection of a citizen’s fundamental rights across the then known world which fell under the sprawling wings of the mighty Roman Empire. Indian citizenship, recently hurled down the throats of recalcitrant Kashmiris, carry a wholly different tag of persecution, hounding and suppression, in all its convoluted forms. The Modi government is endeavouring hard to put the Kashmir issue on the backburner after abrogating Articles 370 and 35-A of the Indian Constitution, which ensconced the Kashmir state in special autonomy and status. The refrain repeated ad-nauseam by Delhi is the “internal” nature of the issue. However, facts speak louder than hollow words, and the indubitable fact is that Kashmir issue is a dispute between India and Pakistan, and recognized as such by the international community.

The “international” nature of the Kashmir dispute can be traced back to Jan 1, 1948, when India knocked the door of UN Security Council and resultantly the Council, via UNSCR 38, called upon the contending governments to refrain from aggravating the circumstances and report any material changes on the ground. Thereafter, the Security Council over a number of years issued a total of 17 resolutions on the dispute of Kashmir. UNSCR 47 of 1948, the most important of the Kashmir resolutions, calls for the resolution of the dispute of Kashmir’s accession to either India or Pakistan through effecting the democratic method of a free and impartial plebiscite. The recently closed-door conclave by the UN Security Council on Kashmir re-emphasized the disputed and international nature of the issue.

Simla Agreement of 1972, the premier bilateral accord between the warring nations, holds that “principles and purposes of the Charter of the United Nations shall govern the relations between the countries”, hence shining a light on the validity of the UNSC resolutions on Kashmir. The disputed nature is further reiterated as, “In Jammu and Kashmir, the Line of Control resulting from the cease-fire of December 17, 1971, shall be respected by both sides without prejudice to the recognized position of either side. Neither side shall seek to alter it unilaterally, irrespective of mutual differences and legal interpretations”. And finally, the reference to “a final settlement of Jammu and Kashmir” again upholds the contended nature of Kashmir issue between India and Pakistan. The international aspect of the dispute is affirmed when differences between the two nations are to be resolved “through bilateral negotiations or by any other peaceful means mutually agreed upon between them”. The Lahore Declaration of 1999 also spotlighted the fundamental disputed issue of Kashmir as the main hurdle towards ensuring peace and prosperity in the region.

The international and disputed nature of Kashmir is further highlighted by the establishment of the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) in January 1949. The UN military observers have had a continuous presence along the LOC for the last four decades, since the ceasefire of December 17, 1971. China claims a part of the disputed territory in Ladakh, and President Trump has repeatedly offered to mediate for a settlement. This shows that the world accepts the Kashmir issue as an international dispute.

Apart from the specific UN resolutions which guarantee Kashmiris’ the right to self-determination, the UN Charter in Article 1(2) declared one of its purposes as, “To develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples”. This serves as the biggest impetus to the said right under international law. In 1952, the General Assembly further expounded this principle and stated in Resolution 637A(VII), that ‘the right of peoples and nations to self-determination is a prerequisite to the full enjoyment of all fundamental human rights’ and recommended that UN members ‘shall uphold the principle of self-determination of all peoples and nations’. The Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples enshrined in GA resolution 1514 of 1960 upheld the right to self-determination. The resolution explicitly says, “All peoples have the right to self-determination; by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development”.

The principle of self-determination was given overwhelming protection in Article 1 of both International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). In 1966, these two covenants enshrined the self-determination principle verbatim as was laid in GA resolution 1514. The Declaration of Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations (GA Resolution 2625 of 1970) went further in recognising that peoples resisting forcible suppression of their claim to self-determination are entitled to seek and receive support in accordance with the purposes and principles of the Charter. Since the adoption of the Declaration in 1970, the ICJ has, on a number of occasions, confirmed that the principle of self-determination constitutes a binding norm of customary international law and even a rule of jus cogens- the peremptory rule of international law. Thus, international law and the specific UNSC resolutions on Kashmir uphold and provide the Kashmiris with the overriding principle of the right to self-determination.

Modi government should hearken the words of the British statesman Edmund Burke, spoken at the time of struggle for independence by Britain’s colonies in America, “the use of force alone is but temporary. It may subdue for a moment, but it does not remove the necessity of subduing again; and a nation is not governed, which is perpetual to be conquered”.