“I never let my left hand know what my right hand is doing.” –Franklin D Roosevelt

The standard version of WWII history tells us that the U.S., which had kept itself out of the war, was forced to enter WWII because of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The assiduously hidden truth, buried under the lies of “standard” history books, tells us that the Japanese were deliberately provoked into attacking Pearl Harbor by the Roosevelt administration. The documents outlining the hideous plan of deceiving Japan into attacking the U.S. were obtained by Robert B. Stinnett (1924-2018) under the Freedom of Information Act in January 1995. He disclosed his remarkable findings in a book The Day of Deceit: The Truth About FDR and Pearl Harbor published in the year 2000. It took 16 years for Stinnett to complete his research!

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR), who belonged to a family which had deep roots in banking and business, and who had Jewish ancestry, had surrounded himself by a very large number of Zionist cum Communist Jewish advisors, all of whom wished to destroy Germany by using American power. FDR had been secretly engaged in persistent intrigue and treasonous attempts at provoking Germany into attacking the U.S. His sordid and criminal attempts at achieving this goal failed because Adolf Hitler showed remarkable restraint.

Let us quote Professor Revilo P. Oliver from his book America’s Decline: The Education of a Conservative: “His [FDR’s] first plan was defeated by the prudence of the German government. While he yammered about the evils of aggression to the white Americans whom he despised and hated, Roosevelt used the American Navy to commit innumerable acts of stealthy and treacherous aggression against Germany in a secret and undeclared war, hidden from American people, hoping that such massive piracy would eventually so exasperate the Germans that they would declare war on the United States, whose men and resources could then be squandered to punish the Germans for trying to have a country of their own.”

The above assertion of Professor Oliver is based, among other things, on the revelations made by the U.S. naval historian Patrick Abbazia. Professor Oliver writes: “These foul acts of the War Criminal [FDR] were known, of course, to the officers and men of the Navy that carried out the orders of their Commander-in-Chief, and were commonly discussed in informed circles, but, as far as I know, were first and much belatedly chronicled by Patrick Abbazia in Mr. Roosevelt’s Navy: The Private War of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, 1939-1942, published by the Naval Institute Press in Annapolis in 1975. The shocking facts are reported in that book, with only daubs of rhetorical whitewash applied perfunctorily here and there to disguise a little the hideous caput mortuum of the traitor, but with no intention of deceiving the alert and judicious reader.”

Despite massive propaganda in the Zionist run media and despite efforts by Hollywood, the U.S. public did not wish to join the war. Then, on September 27, 1940, the three powers, Germany, Japan and Italy signed an agreement whereby an attack on any one of the three would be considered an attack on all three. This was a godsend for FDR who was itching for war, not in the interest of the U.S., but for his own tribe. He, as Professor Revilo Oliver has noted, hated white Americans. Ten days later, on October 7, 1940, FDR received a detailed plan for provoking Japan into attacking the U.S. Having failed to provoke Germany, FDR went ahead with the plan to provoke Japan. It had been prepared by Arthur H. McCollum, head of the Far-East desk of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI).

According to declassified documents McCollum had proposed the following eight-point plan, which, he was certain, would provoke Japan to attack. A photograph of the four-page document appears in Stinnett’s book. It outlines the following eight-point action plan: “A) Make arrangements with Britain for use of British bases in the Pacific, particularly Singapore; B) Make an arrangement with Holland for the use of base facilities and acquisition of supplies in the Dutch East Indies [now Indonesia]; C) Give all possible aid to the Chinese government of Chiang Kai-shek; D) Send a division of long range cruisers to the Orient, Philippines or Singapore; E) Send two divisions of submarines to the Orient; F) Keep the main strength of the U.S. Fleet, now in the Pacific, in the vicinity of Hawaiian Islands; G) Insist that the Dutch refuse to grant Japanese demands for undue economic concessions, particularly oil; H) Completely embargo all trade with Japan, in collaboration with a similar embargo imposed by the British Empire.” McCollum’s note ended with the following words: “If by these means Japan could be led to commit an overt act of war, so much the better. At all events we should be fully prepared to accept the threat of war.”

On October 8, 1940, a day after receiving the McCollum proposal, FDR held an extended luncheon meeting with Admiral James O. Richardson, Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet. Richardson headed both, the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets. He was opposed to the policy already being pursued by FDR of keeping the U.S. Navy in the Pacific around Hawaii and had sought the meeting to end this “illogical” policy. He had 217 ships and 69,000 sailors in the Pacific Fleet and was concerned about their security. When FDR suggested action F i.e. keeping the U.S, Fleet in Hawaiian waters, Admiral Richardson was disturbed because FDR had not taken him into confidence about his intentions, He was exasperated and asked, “Are we here for a stepping-off place for belligerent activity?” He felt that such a move would provoke Japan. Richardson knew that Japan was run by military men who would evaluate and interpret U.S. actions in military terms.

As noted by Stinnett, “Richardson missed the point. White House strategy was based precisely on the premise that Japan’s militant right wing would push for an act of force against the United States.” Richardson was to state later: “I came away with the impression that, despite his spoken word, the President was fully determined to put the United States into the war if Great Britain could hold out until he was reelected.” During the lunchtime meeting he also disagreed with FDR’s proposal to sacrifice a ship of the Navy in order to provoke a Japanese “mistake”. Richardson, at one point exploded: “Mr. President, senior officers of the Navy do not have the trust and confidence in the civilian leadership of this country that is essential for the successful prosecution of a war in the Pacific.”

Admiral Richardson’s resistance sealed his fate and FDR decided to quietly get rid of him. He did so in January 1941 by “restructuring” the Navy. He broke the unified command of the U.S. Navy into two independent commands – a two-ocean Navy was set up, with separate heads for the Pacific Fleet and the Atlantic Fleet. Junior officers, who would be obsequious towards FDR, were chosen to head the two Navies. “Skipping over more senior naval officers the President picked Rear Admiral Husband Kimmel to head the Pacific Fleet and promoted him to a four-star rank. The job had been offered to Rear Admiral Chester Nimitz in the fall of 1940 but Nimitz `begged off’ because he lacked seniority.”

Stinnett points out that in September 1940 and in the first week of October 1940, U.S. cryptographers broke the Japanese diplomatic codes as well the Japanese naval codes. This was a major breakthrough. Interestingly, the breaking of the naval codes, which played a key role in the Pearl Harbor deception, is not generally mentioned in literature, which seems to emphasize merely the diplomatic codes. Because of the success in breaking military codes the U.S. knew exactly what was being planned by the Japanese naval and military leadership.

Three of McCollum’s actions were already in place by January 1941. Twenty-four U.S. Navy submarines were on way to Manila (action E), the Pacific Fleet ships in Hawaii (action F), and the Dutch refusing to provide oil and raw materials to the Japanese. Relations between the U.S. and Japan were therefore rapidly deteriorating. A diplomatic radio message of January 30, 1941, sent by the Japanese Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka to the Japanese ambassador in Washington stated: “In view of the critical situation between the two countries we must be prepared for the worst.” He directed the ambassador to switch from publicity and propaganda work to espionage activity. Matsuoka desired “details on the movement of warships, and on military maneuvers, and figures for aircraft production and shipbuilding throughout the United States.”

Within a month of McCollum’s proposal, the Japanese Naval Minister Admiral Koshiro Oikawa promoted Vice Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto to the rank of Admiral and entrusted him with the command of the Imperial Japanese Navy. At a meeting held between the two, it was agreed to launch a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. By mid-January 1941 Yamamoto had drawn his plan and had assigned various duties to various officers in this regard. The attack was to be launched in case the Japanese faced a worst of worse situations. The plan leaked because Yamamoto circulated it among trusted officers of the Navy.

In the last week of January 1941, Max W. Bishop, Third Secretary at the U.S. embassy in Tokyo was standing in a line waiting to convert some dollars to yen, when Dr. Ricardo Rivera Schreiber, a Peruvian minister to Japan, tapped him on his shoulder. Dr. Schreiber took him aside and told Bishop that the Japanese were planning to launch a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in case of trouble with the U.S. Bishop rushed to the embassy and conveyed this stunning information to his ambassador Joseph Grew. The ambassador then sent the following message to Cordell Hull, Secretary of State, who read it the following morning, January 27, 1941.

“My Peruvian colleague told a member of my staff that he had heard from many sources including a Japanese source that the Japanese military forces planned in the event of trouble with the United States, to attempt a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor using all of their military facilities. He added that although the project seemed fantastic the fact that he had heard it from many sources prompted him to pass the information. Grew” Cordell Hull circulated the note among army intelligence and ONI. The note, when seen by McCollum, showed him that his plan was working. But he did not alert the naval authorities in Hawaii and instead dismissed Grew’s information as “rumor”! He was deceiving his Secretary of State and his Pacific Fleet Naval Chief Admiral Kimmel! He and FDR knew what was going on but Kimmel was out of the loop and would face disaster eventually.

In order to mislead the Japanese, FDR indulged in another exercise in deception which is mentioned by Professor Revilo P. Oliver. In January 1941, FDR summoned the Portuguese Ambassador to the U.S., and, in feigned secrecy, asked him to most confidentially convey to Premier Salazar, that Portugal need not worry about its colonies in the Far East, like East Timor, because, the U.S. intended to destroy Japan once and for all, by launching a massive and irresistible attack, once Japan’s lines of communication were stretched to the limit. In the words of Professor Oliver: “As expected, the Portuguese Ambassador communicated the glad tidings to the head of the government, using his most secure method of communication, an enciphered code, which the Portuguese doubtless imagined to be ‘unbreakable’, but which Roosevelt well knew had been compromised by the Japanese, who were currently reading all messages sent in by wireless.” The Japanese had read the message and were led to believe that the U.S. intended to attack Japan at an opportune moment. The trick had succeeded because the Portuguese message was soon mentioned in an encrypted Japanese communication, which the Americans could read,

FDR and his closest confidantes were simultaneously deceiving Japan, the people of the U.S., and the Naval command at Hawaii. Admiral Kimmel had assumed charge on February 1, 1941. Soon Captain Anderson, whom FDR knew, was promoted as Rear Admiral and placed in charge of the Pacific Fleet battle ships. Anderson had little respect among fellow officers and was not a distinguished sailor. Anderson knew about the McCollum memo but did not tell his boss Admiral Kimmel about it.

Admiral Kimmel had sensed within a couple of weeks of assuming charge that he had been excluded from the intelligence loop. On February 18, and again on May 26, he wrote to Admiral Stark in Washington asking for fixing of responsibility for dissemination of reports of a secret nature. On both occasions his requests were ignored. According to Stinnett, “By late July 1941, he had been cut off completely from the intelligence generated in Washington.” He was being treated as a pawn in a game being played by FDR and his close confidantes.

On account of complete coordination between the U.S., Britain and the Dutch, difficulties for Japan increased. Stinnett notes: “Throughout the summer and spring of 1941, the White House manipulated the oil negotiations. On March 19, Roosevelt met with Netherlands Foreign Minister Dr. Eelco van Kleffens in the Oval Office. Van Kleffens, Roosevelt and Undersecretary of State Summer Welles conferred for several minutes and reiterated the strategy for frustrating Japanese acquisition of petroleum products as advocated by McCollum’s actions B and G.”

To further complicate things for Japan the Dutch permitted oil supplies to Japan but at a diminished rate. Further they required the Japanese to use their own oil tankers to transport oil and to pay for them in dollars. The New York Times reported that “Japan was enraged.” That precisely was the objective. Japanese negotiations with the Dutch authorities did not succeed, adding to their frustration. They were told that it were the oil companies, and not the Dutch government, that controlled oil sales.

Japanese frustration was building up and in an October 16 message that was intercepted by the U.S., the Japanese foreign office urged quick seizure of the Dutch possessions in East Indies. The intercepted message stated: “The United States is incapable of taking action at the present time to prevent Japanese seizure of the Dutch possessions in the Far East and no time should be lost in effecting such a seizure.” Since negotiations had failed to get Japan the desired oil and minerals, they had decided to simply seize the Dutch possessions militarily. An October 25 message revealed that the Japanese wished to lease ground for a technical base to be manned by the military in disguise, and then to use it for military operations against the Dutch. The message was relayed to the Dutch by the Americans and the lease was refused.

The Japanese were being increasingly driven to desperation and they knew, and had told the Dutch that they were creating difficulties under American influence. One must bear in mind that FDR regime had implanted the seed in the Japanese mind that the U.S. intended to attack Japan. For this purpose, the Pacific Fleet battle ships had assembled at Hawaii by April. FDR had himself taken charge of sending cruisers close to the Japanese waters, “pop-up” cruises as he called them. FDR told Kimmel “I just want them to keep popping up here and there and keep the Japs guessing. I don’t mind losing one or two cruisers, but do not take a chance on losing five or six.” Admiral Kimmel, who was not in the loop, objected by saying: “It is ill-advised and will lead to war if we make this move.” But that is what FDR wanted – this was action D suggested by McCollum. So the Japanese assessed that the U.S. wanted to attack Japan.

When, in October, the intercepted Japanese communications suggested seizure of Dutch Far Eastern possessions, FDR had already discussed this with Admiral Richardson. The Admiral had asked FDR on October 8, if the U.S. was going to enter the war. In his words: “He [FDR] replied if the Japanese attacked Thailand, or the Kra peninsula, or the Dutch East Indies we would not enter the war, that if they even attacked the Philippines he doubted whether we would enter the war, but that they could not avoid making mistakes and that as the war continued and the area of operations expanded, sooner or later they would make a mistake and we would enter the war.” Had the Japanese known this they would never have made the mistake of attacking Hawaii. But then the secret Portuguese message told them, falsely, that the U.S. intended to crush Japan by attacking it an appropriate time. And other actions advised by McCollum suggested the same!

Two different stations in Hawaii dealt with Japanese naval intercepts, station H and station HYPO. Station H intercepted the messages and then these were decoded at station HYPO. From mid-November on the intercepted messages and radio direction finders showed that carrier Division Three and Four of the Imperial Japanese Navy were headed for South-East Asia. But Divisions One, Two and Five were headed for Hawaii. The messages intercepted by station H between November 18 and December 1, 1941, as well as well as their radio logs for the same period, as interpreted by HYPO provide powerful evidence of the U.S. foreknowledge of the impending Japanese attack.

Stinnett points out: “Americans do not know these records exist – all were excluded from the many investigations that took place from 1941 to 1946, and the Congressional probe of 1995.” Why were these records concealed from the inquiries and from the Congress? Simply because they revealed foreknowledge of an attack in which approximately 3,000 lives were lost and ships sunk or damaged. Two radio messages from Admiral Yamamoto ordered the Japanese fleet to depart from Hitokappu Bay on November 26 and advance towards Hawaii.

The first message in the said records was as follows: “The Task Force, keeping the movement strictly secret, shall leave Hitokappu Bay on the morning of 26th November and advance to 42o N. X 170o E. on the afternoon of 3 December and speedily complete refueling.” The second dispatch was as follows: “The Task Force keeping its movement strictly secret and maintaining close guard against submarines and aircraft, shall advance into Hawaiian waters, and upon the very opening of hostilities shall attack the main force of the United States Fleet in Hawaii and deal it a mortal blow. The first air raid is planned for the dawn of X-day. Exact date to be given by later order.”

The dispatch continues: “Upon completion of air raid, the Task Force, keeping close coordination and guarding against the enemy’s counterattack, shall speedily leave the enemy waters and then return to Japan. Should the negotiations with the United States prove successful, the Task Force shall hold itself in readiness forthwith to return and reassemble.” The two message quoted above are among many other intercepts that confirm that the Japanese fleet was headed for Hawaii.

On November 28 Admiral Stark sent Admiral Kimmel instructions that included the following highly important order: “If hostilities cannot be avoided the United States desires that Japan commit the first overt act.” FDR wanted the people of U.S. to feel that they had been attacked unaware and that would generate an immense response in favor of joining the war. This is exactly what happened. These orders tied Kimmel’s hands completely. He could not advance to meet the Japanese in open seas, nor could his aircraft attack Japanese ships. His fleet became a sitting duck at Hawaii, as intended by FDR. Nine military commanders had received warnings of impending attacks, such as in Philippines – seven of them responded by putting their forces on alert. Hawaii was the only exception.

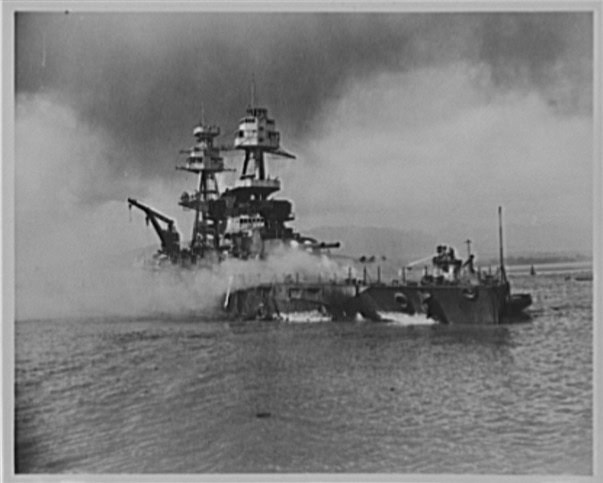

When the Japanese were able to successfully attack Hawaii on December 7, 1941, the U.S. was taken by storm and FDR got what he wanted. But Admiral Kimmel, and his counterpart in army, paid a very heavy price. They were relieved of their commands for negligence of duties. The fact is that both of them were denied vital information and the hands of both were tied by orders originating from FDR. But the public did not know this with the result that both faced disgrace in the eyes of the public. FDR had used both of them to achieve his goal.

In his book The Curse of Canaan, Eustace Mullins writes: “It seemed everyone in in a position of authority in London and Washington knew that the Japanese intended to attack Pearl Harbor, which was hardly surprising, because the Japanese secret codes had been broken months before. The nightmare of the plotters was that the Japanese commanders might inadvertently find that their codes had been broken and call off the attack on Pearl Harbor, since they would know that the defenders would be warned. The Washington conspirators while breathlessly following the course of the Japanese fleet towards Pearl Harbor, avoided intimating to Kimmel and Short, the American commanders in Hawaii, that they were in any danger. Alerting them, of course would warn the Japanese and cause them to turn back. The Japanese commanders later said that at the first sign of alarm, they were prepared to turn back toward Tokyo without pressing their attack.”

It was only in 1999 that the U.S. Senate posthumously cleared Adm. Husband Kimmel (1882-1968) and Gen. Walter Short (1880-1949) through a resolution stating that they had performed their duties “competently and professionally” and that U.S. losses Pearl Harbor were “not the result of dereliction of duty.” The Senate accepted that “They were denied vital intelligence that was available in Washington.” The resolution resulted from the relentless efforts of the Kimmel family to clear the name of their family member. who Senators William V. Roth Jr. (R-Del.) and Strom Thurmond (R-S.C.) called Kimmel and Short “the two final victims of Pearl Harbor.”