By: Ms Manal Shah

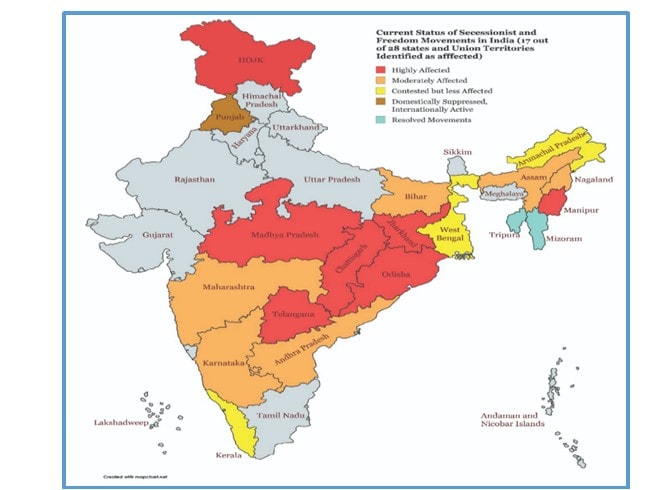

Despite its “largest democracy” claim, India faces rising internal conflicts through secessionist and freedom movements rooted in mass alienation and state mistrust. This Insight examines their origins, current status, and the state’s military, political, legal, and media responses amid growing domestic radicalism.

In India’s Northeast, post-independence integration failures have fuelled enduring secessionist movements, such as those in Nagaland, Manipur, Assam, Mizoram, and Tripura.

Naga movement is rooted in identity-based grievances and refusal to join India due to state negligence, leading to the independence declaration (1947). Despite gaining so-called statehood (1963), key concerns remain unresolved. State-led Shillong Accords (1975), ceasefire (1997) and framework agreement (2015) have collapsed, leading to deadlocked negotiations, splits in liberation factions, and increased demand for Greater Nagaland.

Manipur’s conflict stems from ethnic tensions between dominant Meiteis and over 30 hill tribes with Scheduled Tribe (ST) status. Kuki-Zomi and Naga tribes, mostly Christian, sought autonomy, while Meiteis, predominantly Hindu and excluded from ST status, formed a liberation front (1964). Despite a ceasefire (2008), deadly Meitei-Kuki clashes reignited (2023), fuelled by alleged bias from Meitei-led BJP-backed institutions. Despite troop deployments (40,000) and administrative division, peace remains elusive.

| Persistent secessionist and freedom movements across India highlight unresolved injustice and state apparatus increasingly reliant on exclusion and repression over reforms and stability. |

Assam movement (1979) stems from ethnic nationalism and fears of cultural erosion and economic marginalisation due to large-scale migration from Bangladesh. Groups like United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) have sought independence (1979), citing state neglect and threats to Assamese identity. Despite Assam Accord (1985), unrest has persisted. The ULFA-Arabinda faction signed peace deal (2020), but Baruah-led faction remains active.

In central-east, Naxalite movement began in Naxalbari, West Bengal (1967) as an armed struggle for land and tribal rights, spreading across underdeveloped “Red Corridor.” It remains low-intensity movement calling for revolutionary change. Peaking around 2009-2010, it now faces state crackdowns, with BJP-led government accused of staged encounters and forced tribal evictions.

Mizoram movement began after state neglect during the 1959 famine, highlighting state’s disconnect with peripheral regions. After a call for independence (1961) and decades of unrest, a peace accord (1986) led to its statehood (1987).

Secessionist and Freedom Movements in India

Source: Self Compiled

Tripura movement (1980s), rooted in tribal resentment over loss of land, identity, and political power mainly due to large-scale migration from Bangladesh, demanded secession for indigenous Tripuris. Violence weakened (2000s) due to peace accords, surrenders, and partial autonomy (2024).

Towards India’s west, Khalistan freedom movement arose (1970s-80s) by Sikh alienation, economic marginalisation, and state repression, intensifying after Indian military’s Operation Blue Star (1984), followed by over 500 killings and 2,097 secret cremations by Amritsar police. Despite their historical rule in Punjab, denial of a Sikh-majority state was seen as a cultural erasure. Though it is largely suppressed internally through a combination of military operations, stringent policing and political engagement, periodic flare-ups, and diaspora-linked activism persist. BJP’s targeting of activists abroad raised concerns over India’s breach of international norms to serve domestic political agendas.

Kashmir freedom movement began (1947) after India denied self-determination to its Muslim-majority population, sparking one of world’s oldest and biggest disputes. India’s occupation of disputed territory has involved mass repression and highest troop deployment in any civilian area (900,000 – MOFA 2021), with widespread human rights abuses, including enforced disappearances, rapes, detentions, tortures, and extrajudicial killings. Before 2019, India maintained the special status of Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK) in line with its obligations under UN Security Council resolutions. The BJP government unlawfully revoked Indian constitution’s Articles 370 and 35A provisions that granted the region internal autonomy and exclusive rights for its permanent residents. Worsening the crisis, it was an attempt to alter Kashmir’s status from a multilateral issue under UN resolutions to a bilateral Pakistan-India matter under the Simla Agreement, and ultimately to a unilateral decision by India.

Indian state’s response to these movements has largely been coercive, marked by heavy military deployments and use of force. In cases like Kashmir, Manipur, Red Corridor, and Khalistan, security forces have been central to state’s response. While this may have brought temporary order in some cases, it has mostly intensified resentment and perpetuated cycles of violence; recent offensives, such as “Operation Zero” (2025) against Naxalites, is a case in point.

Politically, India has demonstrated selective willingness to negotiate. Peace accords and autonomy arrangements in Mizoram, Tripura, and Assam (partial) yielded some results. However, the state exploits internal divisions by supporting pro-centre governments, splinter factions, and surrender schemes more as control mechanisms than genuine reconciliation. For instance, around 300 people were killed in Assam (1998-2001) as police and army units exploited rehabilitation schemes, employing surrendered cadres to execute extrajudicial mass killings.

Several movements have seen a mix of military responses, like “scorch earth policy” for Nagaland, and political dialogue, yet they remain unresolved due to unmet demands.

Legally, Indian state has expanded use of stringent laws, such as sedition clauses (1870-British colonial law), Armed Forces Special Powers Act (1958), Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (1967), Public Safety Act (1978), National Security Act (1980), and Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (1985), to suppress movements. They enable prolonged detention and target activists, journalists, and minority voices. Legal repression, framed as national security, undermines civil liberties and fuels domestic and international concerns over democratic decline.

Media censorship and internet blackouts are common. Mainstream Indian media often distorts or downplays movements, playing key role in shaping public opinion against them for political gains. By framing them as foreign-sponsored threats, e.g., branding Kashmir freedom struggle as “Pakistan-sponsored terrorism” and Naxalite as “Maoist extremism” the state controls narratives, masking its inability to address issues. This delegitimises genuine grievances, justifies crackdowns, and silences dissent, while media critics face harassment, censorship, or legal action.

Tensions have worsened under BJP-led government. A Hindutva-driven agenda has further sidelined and marginalised minorities. Use of harsh laws and stalled peace processes has made political resolution increasingly elusive. Rising communal polarisation continues to erode the social fabric. Since PM Modi took office, there has been a marked increase in hate speeches and crimes, press restrictions, and discriminatory laws. International watchdogs now categorise India as a “flawed democracy,” citing steady erosion of civil liberties and democratic norms.

Despite this, global powers have largely overlooked India’s authoritarian drift, prioritising its role as a counterweight to China. But if India’s apparent economic momentum slows or its strategic utility declines, this overlooked vulnerability could invite global scrutiny and even external leverage in the form of strategic manipulation. All this is leading to regional instability, as seen in the form of uncalled-for Indian provocations in May 2025.

The writer can be contacted at manalshah2002@gmail.com