By: Noor Ul Ain Tahir

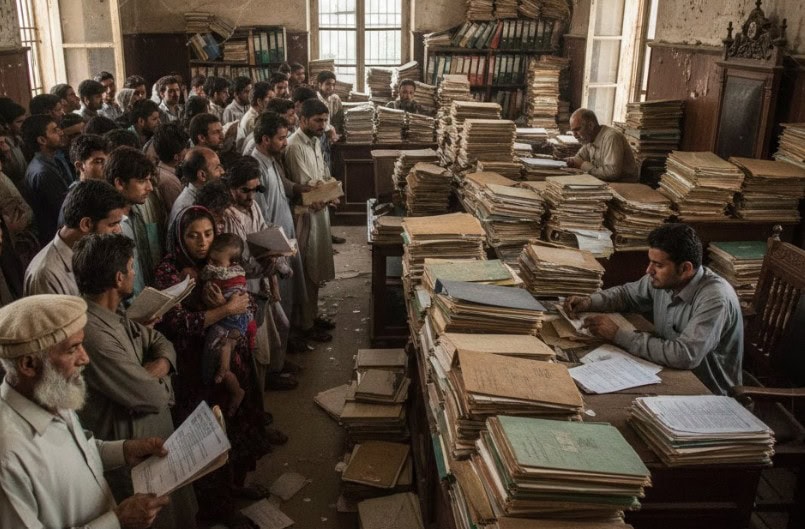

Justice delayed is justice denied. This saying embodies the core issue of Pakistan’s judicial system, where the backlog of cases increases daily with no immediate solution. Pakistan has a multi-tiered court structure, with the Supreme Court at the top, followed by High Courts, Federal Shariah Court, and Lower Courts. The lower judiciary, comprising District and Session Courts, deals with civil and criminal cases, respectively. These courts bear the heaviest burden, with 1.86 million pending cases compared to 0.39 million at the higher levels in 2025. Civil cases in the district judiciary make up 64% of this backlog. Therefore, this insight focuses on district courts, examining the causes of backlog, past reforms, and why a solution remains elusive.

A ‘backlog’ is: “number of pending cases not resolved within an established timeframe.” Although no time limit is specified in the law, the National Judicial Policy-Making Committee (NJPMC) has given deadlines for case disposal. For instance, 12 months to close civil court decrees. When these timelines are not met, the resulting accumulation of unresolved cases constitutes a backlog.

Emerging studies suggest that the backlog of civil cases may be contributing to rising crime rates as delayed justice pushes people to take matters into their own hands.

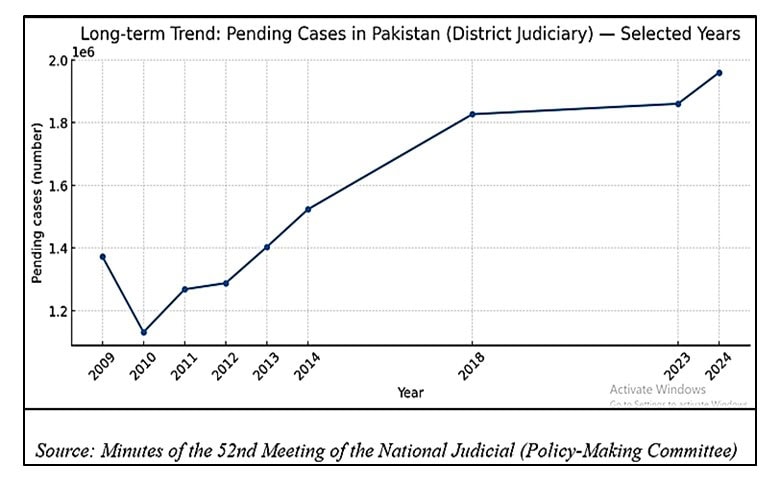

In Pakistan, the issue of backlog is concerning. The following graph illustrates the trend of backlog in the district judiciary over the past 15 years: The National Judicial Policy (NJP) was introduced in 2009 under the leadership of then Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry. It was a judicial reform plan developed by NJPMC. The policy established timelines for case disposal and mandated that all cases filed before December 31, 2008, must be resolved within one year.

This initiative achieved moderate success in 2009, resulting in a 13.7% reduction in backlog. However, once the extraordinary push eased and leadership changed, the underlying problems reasserted themselves, and pendency rose again.

|

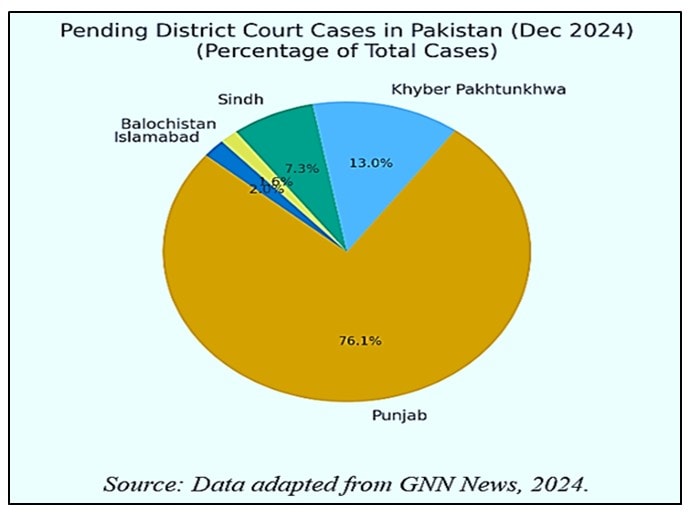

This pattern is most visible at the provincial level. The chart below presents a province-wise breakdown of pending cases in distric courts. However, very little to no data is available regarding Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) and Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJ&K).

After conducting research, it appears that vacant judicial posts, frequent transfers, infrastructure deficiencies, and corruption are the primary factors contributing to backlog.

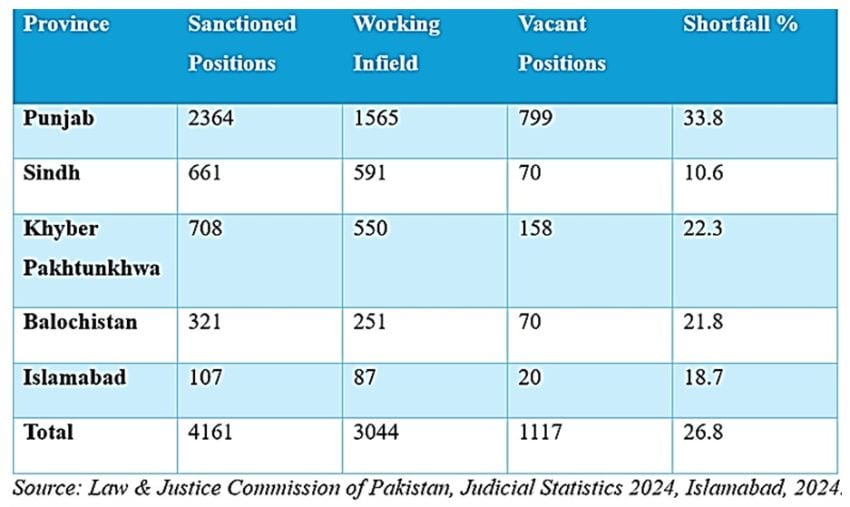

One of the primary obstacles driving the backlog is the shortage of judges. This stems from slow, politicised appointments, delays in filling vacancies, and budgetary limits on recruitment, all of which reduce judicial productivity. The following table presents judicial vacancy statistics in Pakistan’s district judiciary for 2024.

Frequent transfers of judges also hinder administration of justice. When judges who have heard evidence are transferred, the newly appointed judges must restart the proceedings, which delays disposal. For instance, in 2019, the Peshawar High Court reshuffled 129 judicial officers. Later, in 2024, the Sindh High Court transferred 64 civil judges. Most recently, in 2025, the Lahore High Court transferred 53 additional district and sessions judges. These transfers are carried out by the Chief Justice of the respective High Court. Although there is no statutory minimum stationing period, NJP recommends that judicial officers should not be transferred before a three-year tenure at a station.

Corruption also fuels delay, with litigants facing demands for informal payments to expedite or stall cases. The National Corruption Perception Survey (NCPS) ranks the judiciary as third most corrupt sector, after police and tendering/contracting. According to NCPS, citizens in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa were reported to pay the highest average bribe to access the judiciary, approximately Rs. 0.16 million per case in 2023.

Infrastructure deficiency is also an issue: over 200 subordinate courts in Karachi’s judicial complex are housed in an overcrowded, ageing structure lacking basic amenities, which degrades service. Case records remain largely paper-based; for instance, in Lahore in 2011, over 5,000 files were discovered in staffers’ homes because storage was inadequate. Although Sindh and Islamabad have introduced online portals and virtual courts, most districts lack comprehensive digital systems.

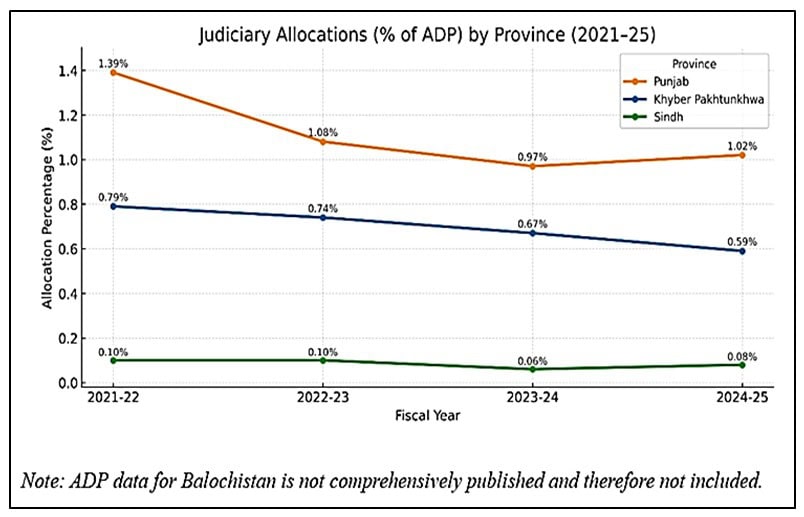

Over the years, the federal government has attempted to strengthen judicial capacity through the Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP), while provincial projects are financed through Annual Development Programmes (ADPs). The graph above shows ADP allocations for Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh and Balochistan.

Despite these fluctuations, judicial infrastructure has not expanded: district courts in Punjab and Sindh still function in overcrowded and rented buildings.

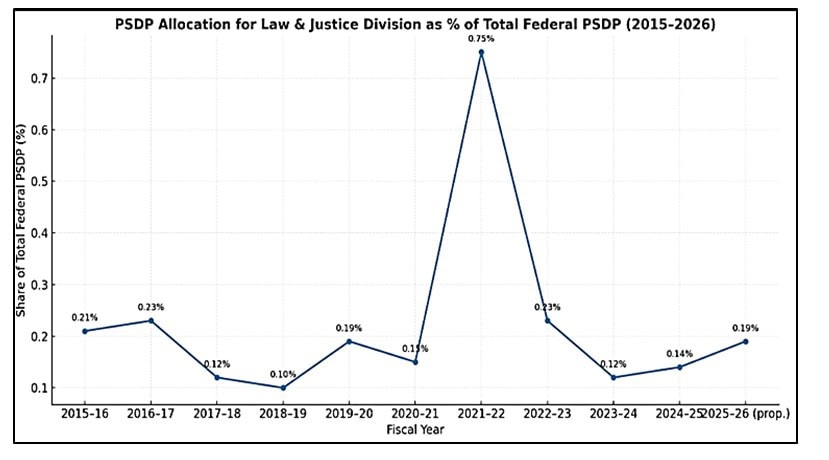

The following graph illustrates PSDP allocations over the past decade, highlighting a sharp spike in 2021–22 when funding surged for 17 projects, including judicial complexes and automation schemes and Islamabad High Court facilities.

To tackle the backlog issue, the Law and Justice Commission of Pakistan (LJCP), a permanent statutory body established in 1979, was tasked with proposing improvements to ensure swift justice. Since its inception, it has regularly issued Annual Reports summarising recommendations on judicial reform and law revision. However, its reports are advisory only; they require adoption by the executive, legislature or judiciary to have effect. As a result, implementation has been weak: in 2017, it was reported that at least 74 out of 138 recommendations were still unimplemented. The News International in 2025 noted that no comprehensive audit of its reports exists, leaving many suggestions unenforced.

In 2019, to expedite cases pending for more than five years, model courts were launched, and within their first year, they disposed of 50,743 cases nationwide. But they faced strong resistance (lawyer strikes, procedural/legal objections) and were scaled back rather than permanently adopted.

Given these shortcomings, policymakers have increasingly turned to Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) as a tool to ease pressure on the courts. ADR has long existed in Pakistan’s legal system, beginning with the Arbitration Act of 1940, followed by Section 89-A of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC), empowering civil courts to refer matters to mediation or conciliation, and later the ADR Act 2017, which sought to institutionalise court-annexed ADR.

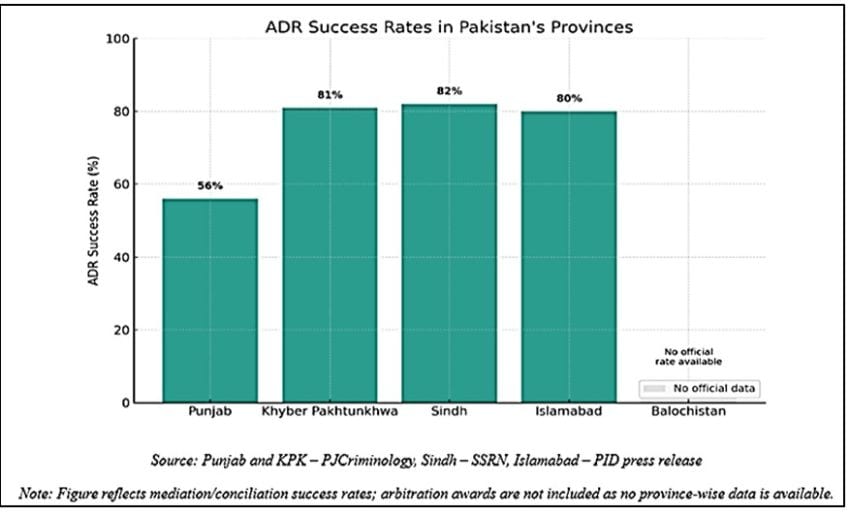

Yet, despite a strong legislative framework, ADR and mediation centres in Pakistan have not reached their full potential. When implemented effectively, they show high settlement rates, for example, in Islamabad, about 80% of cases sent to mediation were resolved without returning to court. Resolution is also faster, Punjab’s ADR centres report most cases concluding within 30–60 days, compared to years in traditional courts. The graph below presents provincial ADR performance.

Still, overall utilisation has remained limited due to the absence of clear referral procedures, inconsistent accreditation and payment systems for mediators and hesitation among litigants to adopt non-traditional processes. But, with stronger institutional support and better implementation, ADR mechanisms can deliver more effective results.

The way forward lies in filling posts promptly, ensuring stable judicial tenures, investing in modern court infrastructure and digitisation, and implementing the Law and Justice Commission’s annual recommendations in full. Only sustained political and judicial commitment can secure timely justice.

The writer can be contacted at: noor10tahir@icloud.com