By: Ms Humna Samad

Education is a fundamental right of every Pakistani citizen. Under Article 25-A of the Constitution, the state must provide free and compulsory education to all children aged

5 to 16. However, according to a 2023 World Bank report, the state falls short in meeting its obligations, enabling the private sector to establish its own education provision. This insight explores the role of private education, from primary to higher secondary, the gaps that have enabled its quick rise, and the shortcomings within its operation.

|

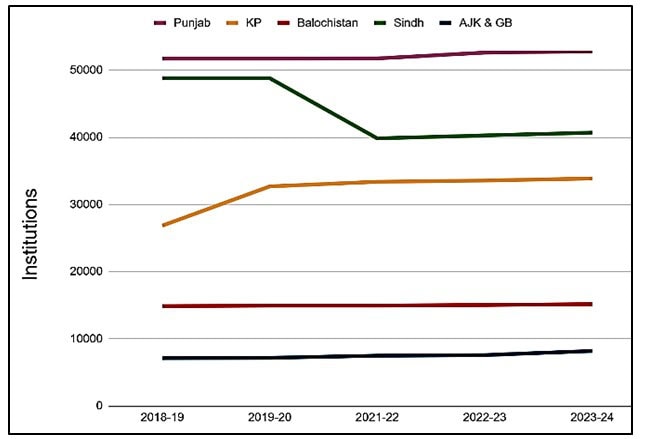

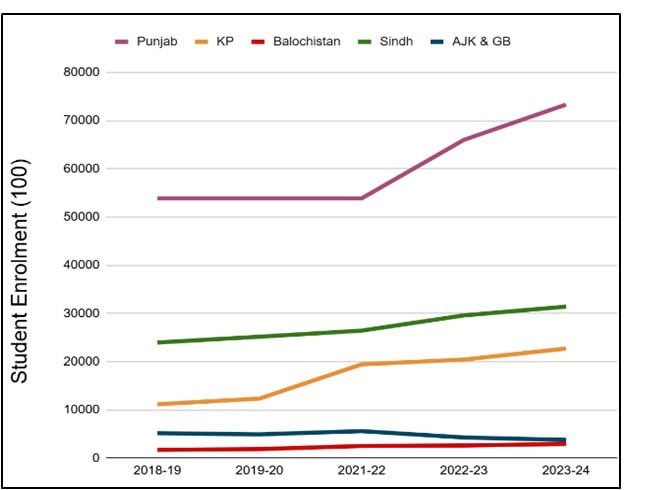

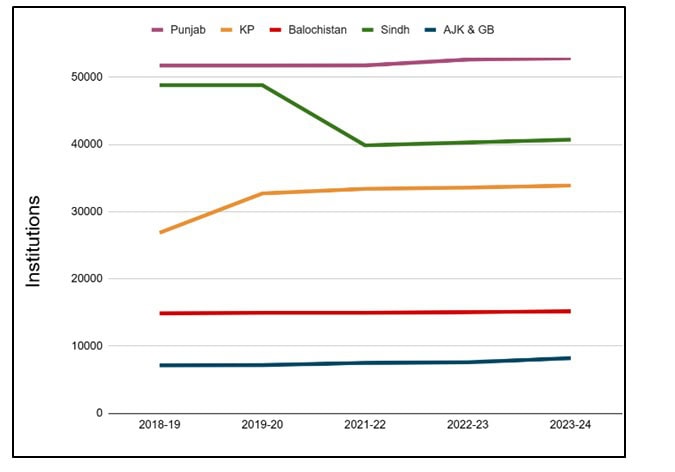

Pakistan’s education system comprises three main streams: public, private, and madrassa. Out of 203,411 institutions, the private sector alone accounts for 60,904 institutions, roughly 30% of all schools and 38% of totalstudent enrolment. The graphs in Figure. 1 show that over the past five years, the number of private sector institutions has grown by 4%, accompanied by a 28% rise in enrolment. In contrast, Figure. 2 graphs demonstrate that public sector institutions have expanded by 6%, but their enrolment has declined by 36%.

Figure 1a: Private Sector Institutions

Figure 2a: Public Sector Institutions

Figure 2b: Public Sector Enrolment

Source: Pakistan Education Statistics 2018-24

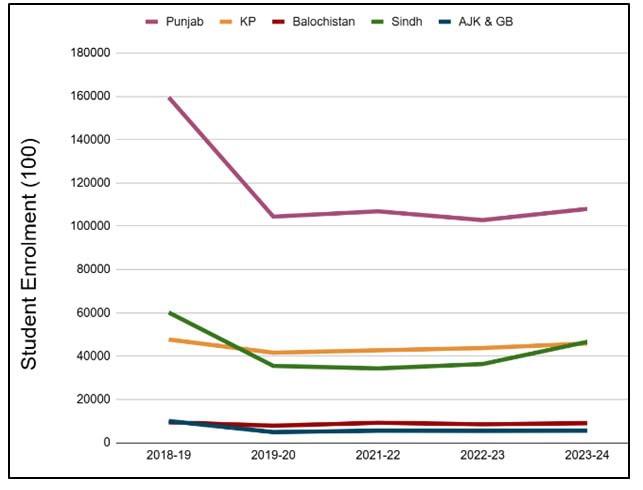

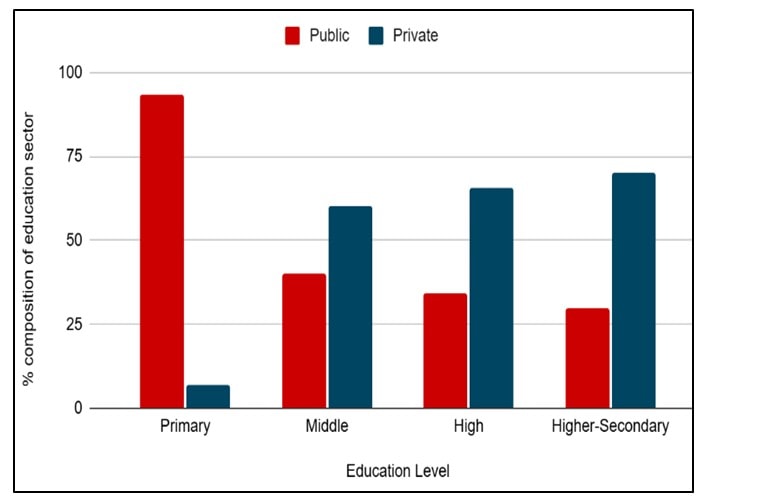

Figure 3 (graph) shows that public schools are overwhelmingly concentrated at the primary level, responsible for over 90% of provision in some provinces. This leaves a vacuum in secondary and higher-secondary education, where private schools have become the dominant providers. This uneven spread has disrupted educational continuity, resulting in only 16% of students appearing in Secondary School Certificate (SSC) exams, as public schooling options become limited.

Figure 3: Distribution across Education Level

Source: Pakistan Education Statistics 2024

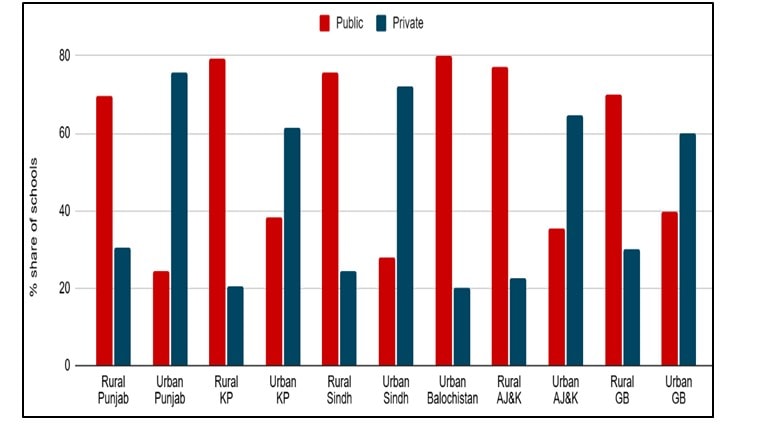

Geographic discrepancies further explain the rise in private education. Figure 4. highlights public school prevalence in rural areas, where they make up more than 70% of provision, but their share falls below 30% in urban centres. With government schools unable to meet city population demand, private institutions have stepped in to establish themselves as the primary education providers in urban Pakistan. This finding proves true for all provinces except Balochistan, where data regarding rural schools remains unavailable.

Figure 4: Regional Distribution of Schools

Source: Pakistan Education Statistics 2024

As the population continues to boom, Pakistan’s education demand also grows. Public sector schools are few, leaving major supply gaps in access across education levels and geographies. This has enabled the private sector to establish its own profitable educational institutions. With enrolment in private schools mushrooming, the sector enjoys high returns, but it has also overburdened classrooms and affected learning outcomes.

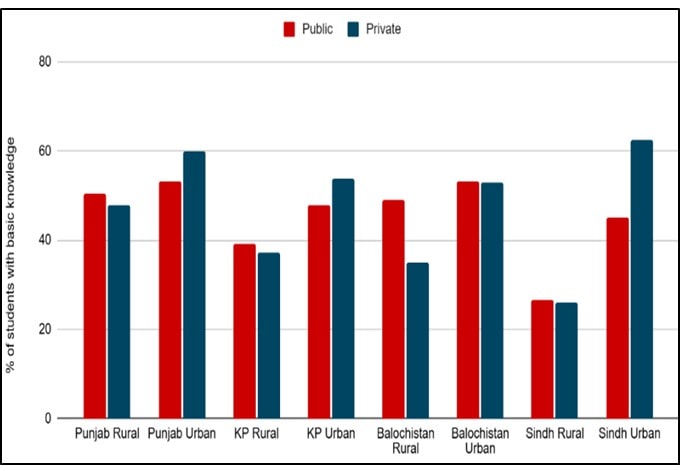

Figure 5 shows that basic learning outcomes for Urdu, English, and Arithmetic remain similar across both sectors. Private schools, which are considered to have superior educational quality, show only a slight advantage of around 5% in urban areas, while public schools perform better in rural districts.

Figure 5: Learning Outcomes across Urdu, English and Arithmetic

Source: ASER (Annual Status of Education Report)- 2024

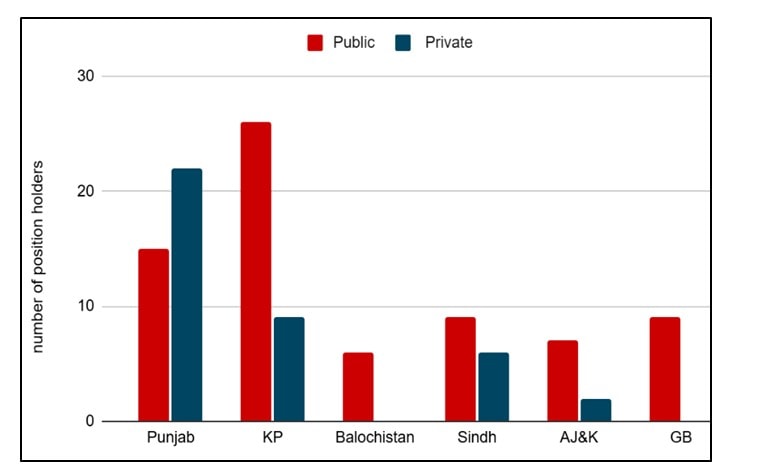

Figure 6 shows the real damage to educational quality due to rising enrolment in private schools. Here, the position holders in the provincial SSC results are dominated by public school students. Only in Punjab, private school students are able to outperform their public school counterparts. Be it learning outcomes or provincial exam results, private schools are performing at unsatisfactory levels, despite having much higher tuition fees than most free public schools.

Figure 6: Position Holders in SSC Exams (2023-2025)

Source: Self-extracted

In light of the above discussion, the role of the private sector in education highlights overarching patterns in access and regulation.

First, with regard to access, the government has consistently fallen short in fulfilling its promise of free and compulsory education under Article 25-A. This has created a space for the private sector to expand its provision. It is unrealistic for the public sector to suddenly provide universal education immediately, especially following the reduction in education spending from 2.1% of Pakistan’s GDP in 2015 to 1.4% in 2024. Still in 2025, the government declared an education emergency, prioritising educational programs that quickly increase enrolment up to the secondary level.

One such initiative is the expansion of Non-Formal Education (NFE) programs, designed to provide vocational training and improve employability for individuals without secondary or higher-secondary schooling. Under Vision 2030, NFE enrolment is targeted to account for 50% of all secondary enrolments. However, these programs cannot substitute formal education, leaving the systemic shortage of secondary provision unresolved. This approach reflects a reliance on private schools to meet secondary and higher-secondary demand, while public institutions make limited efforts to establish new schools. In doing so, the government sidelines its responsibility to guarantee free secondary education for all.

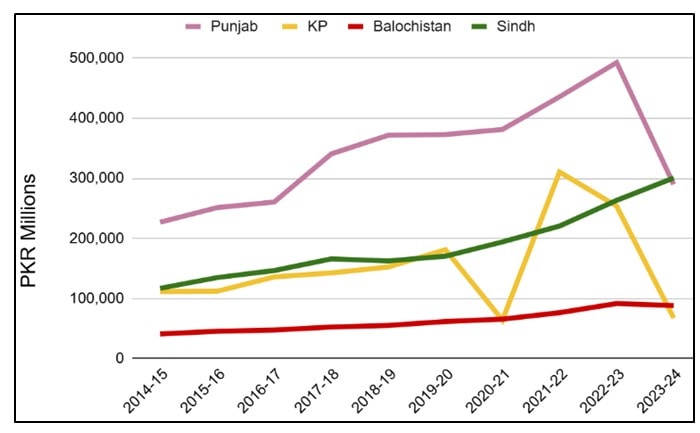

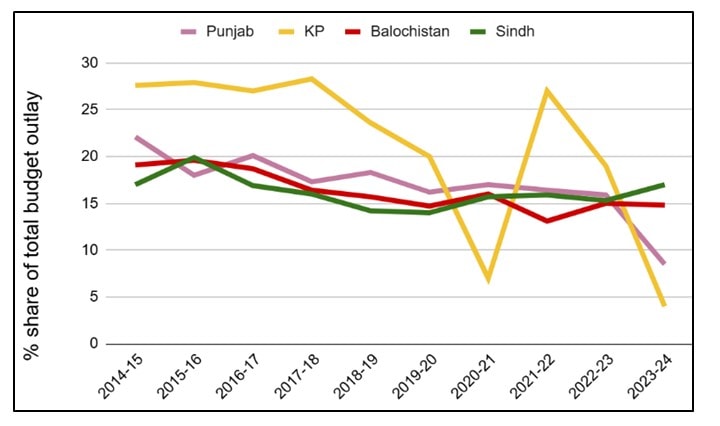

To counter this, Pakistan must enforce stronger policies. Provincial governments should prioritise establishing more urban secondary and higher-secondary public schools to fulfil the constitutional promise of free education. However, Figure 7 shows that despite efforts to increase educational budget, especially by KP, currently, education spending is declining, making it harder to build more schools and keep up with the rising demand for education. Hence, if the government plans to provide complete educational access, it must continue to rely on private schools to meet excess demand until it can increase its budget and establish its own schools.

Figure 7a: Education Expenditure (Millions)

Figure 7b: Education Expenditure

Source: Self-extracted

Secondly, with regard to regulation, private schools’ poor learning outcomes and exam results highlight significant weaknesses in the regulatory framework governing private education. Each province has a dedicated registration and regulatory authority, backed by respective ordinances, which private schools must comply with to establish and maintain their operations. These authorities monitor educational quality primarily through inputs such as teacher qualifications, classroom numbers, and curriculum adherence.

However, this framework is poorly implemented. The education metrics do not directly measure student learning, making it difficult to assess whether true educational quality is being maintained. While regulatory amendments have addressed issues like infrastructure and school fees, standards for academic quality remain largely unchanged. Moreover, these regulatory bodies face limited resources and capacity, and often depend on fees paid by private schools as a continuous revenue flow, raising concerns about their transparency and independence.

To address this issue, private schools must be effectively regulated. New reforms are needed, this time using tangible learning-outcome metrics, such as those provided by the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER). Additionally, to avoid questions on transparency, regulatory bodies must be adequately funded by the government to avoid reliance on fees paid by private schools. Strict oversight and transparency for non-compliance are essential to maintaining quality standards.

Ultimately, the private sector’s rise in Pakistan reflects the deficiencies of the public sector system. While it has filled gaps in access, over-enrolment has compromised its educational quality. Unless the public sector’s expansion and the private sector’s regulation in policymaking are prioritised, the government risks offsetting education disproportionality even more.