The question of creating new provinces in Pakistan has once again become part of the national debate. This discussion is not merely about drawing new lines on the map, but about making governance more responsive, ensuring equitable access to resources, and addressing the long-standing grievances of regions that feel left behind.

In recent sessions of Parliament and provincial assemblies, demands for a South Punjab province and for a Hazara province have resurfaced. Communities in these regions argue that decisions taken in distant provincial capitals often fail to reflect their needs. For them, the demand for a new province is rooted in the desire for timely healthcare, quality education, efficient infrastructure, and employment opportunities that remain scarce under the existing system.

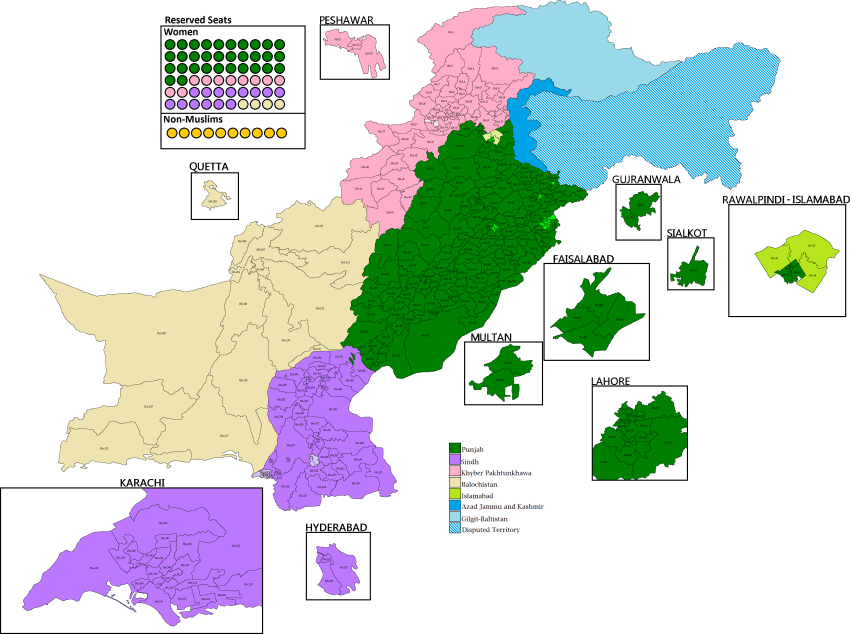

A senior anchor recently compared Pakistan’s provincial structure with India’s. Despite being four times larger in land area and six times more populated, India has 28 states and 8 union territories, while Pakistan remains limited to just four provinces. India’s largest state, Rajasthan, covers about 342,000 square kilometers, which is slightly smaller than Balochistan at 347,000 square kilometers. Punjab, meanwhile, holds nearly half of Pakistan’s population and controls 173 of the 336 National Assembly seats. Such comparisons highlight the concentration of power and resources in a few provinces, and raise important questions about balanced governance.

The advantages of creating more provinces are clear. Smaller administrative units allow for better governance, faster decision-making, and policies that reflect local realities. They empower communities, strengthen citizen engagement, and can foster a stronger sense of national unity. New provinces would also support balanced economic growth, fairer distribution of resources, and reduce regional disparities. With localized administrations, services such as healthcare and education could improve significantly, while infrastructure development, tourism, and investment would receive new focus. This in turn could create jobs, develop skilled workforces, and reduce unemployment. Perhaps most importantly, addressing regional grievances through new provinces could transform discontent into renewed patriotism.

Yet, challenges cannot be ignored. Any move to create new provinces requires a constitutional amendment backed by two-thirds of both houses of Parliament, as well as approval from the concerned provincial assemblies. New bureaucracies, assemblies, and high courts would place financial demands on the state at a time when the economy is already under strain. This means the debate must be approached carefully, with national consensus, and with consideration of both benefits and costs.

Pakistan has changed dramatically since independence—its population has grown many times over, yet its provincial structure remains frozen in time. The question today is whether the existing four-province model can continue to serve the needs of a dynamic and diverse nation. Whether through the creation of new provinces or through meaningful empowerment of local governments, the objective must remain the same: to bring the state closer to its citizens, and to ensure every Pakistani feels represented, served, and included.

For many, this debate is not about politics—it is about fairness, inclusion, and justice. It is about strengthening the federation by giving each region the dignity and recognition it deserves. A Pakistan where no region feels neglected is a stronger, more united Pakistan.