In a world grappling with inequality, charity, a shared precept across diverse faiths, alleviates the miseries of marginalised segments of different societies and reduces disparities. Zakat, a religion-based financial system that eliminates poverty and promotes social well-being, is one of the five pillars of Islamic practice. This insight delves explicitly into Zakat’s collection and disbursement system in Pakistan, highlighting the challenges and offering recommendations for better utilisation of funds.

‘Nisab’ refers to the minimum wealth that makes someone liable to pay Zakat. It is 2.5% of the wealth liable to Zakat. According to the Quran, there are eight recipients (Masarif) of Zakat, including the poor, the needy, debt-ridden, slaves, new Muslims, wayfarers, and those in the cause of God. Zakat administrators are crucial in ensuring the funds reach the intended recipients.

Article 31(c) of the 1973 Constitution of Pakistan and Zakat and Ushr Ordinance 1980 serve as the legal frameworks for the formal Zakat collection system. The Central Zakat Fund (CZF) was established at the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) for centralised collection. The Zakat and Ushr Division, under the Ministry of Finance, managed the Zakat collection system until the 18th Amendment in 2010. This amendment led to a complete restructuring of the system. The management was handed over to the provinces. Provincial Zakat Funds (PZFs) headed by Chief Zakat Administrators were established. District Zakat Committees (DZC) and Local Zakat Committees (LZC) were also formed. The Ministry of Religious Affairs (MoRA) oversees the Zakat collection and distribution by these Zakat Councils.

Investing Zakat funds collected through National Welfare Foundation (NWF) and utilizing the generated revenue to fund institutions can maximize the benefits of Zakat, ensuring sustainable support throughout the year.

The Zakat collection system involves both formal and informal mechanisms. Formally, banks deduct Zakat on the first of Ramadan each year, with exemptions for Fiqh-Jafria. The government annually fixes a new Nisab to deduct Zakat from bank accounts. The collected amount is credited to the CZF in the SBP. Funds from the CZF are then transferred to PZFs and disbursed to districts.

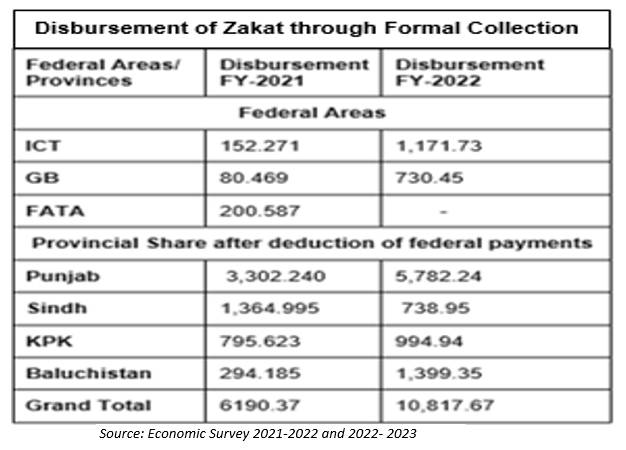

The table displays data about the disbursement of Zakat to Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT), provinces, and Gilgit Baltistan. Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) has its own Zakat and Ushr department, responsible for collection and distribution.

Informally, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), Welfare Foundations, Trusts, and Hospitals also collect Zakat. The funds collected are used for programmes like interest-free loans for the youth, education, skill development, and healthcare, and they enjoy widespread confidence among the people. These are now under government oversight due to FATF regulations. However, the data on their Zakat collection are not available.

Additionally, there is a concurrent decentralised Zakat collection system where people preferably dispense Zakat directly to needy relatives. A survey conducted by the Institute of Business Administration (IBA) Centre for Excellence in Islamic Finance (CEIF) revealed that 95% of Muslims in Pakistan prefer to donate to Shariah-compliant private organisations.

The Zakat system in Pakistan faces several administrative issues, which result in low collection. One of the critical challenges is the omission of modern forms of wealth, such as industrial production and the service sector, for Zakat collection. This may be addressed through ijtihad, if possible. Another challenge is people’s reluctance to institutional collection, as they prefer withdrawing money before the 1st of Ramadan. To address these challenges, banks may devise mechanisms to discourage withdrawals in collaboration with the government and Ulema. These challenges underscore the need for the proposed recommendations to improve the efficiency and transparency of the Zakat system.

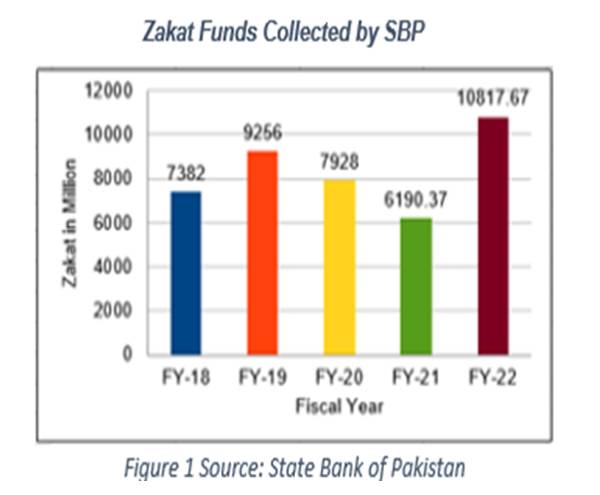

Estimates reveal a promising potential for Pakistan to collect a significant amount through the Zakat system, potentially up to 4% of its GDP. This could translate into a substantial boost in resources for poverty alleviation efforts. However, as per FY-2022, only a fraction of this potential was realised, indicating a significant system efficiency gap. According to the World Bank’s statistics for 2023, more than 37% of Pakistan’s population lives under the poverty line. This stark reality underscores the urgent need for an efficient Zakat system that can play a pivotal role in reducing poverty. With 96% of the Muslim population in Pakistan, an efficient Zakat system holds the promise of a transformative impact on poverty alleviation, instilling hope for a brighter future.

The distribution is also inefficient. Transparency, the absence of clear SOPs for the recipients, and weak management undermine Zakat’s potential. Despite all these challenges, funds are utilised in social welfare programmes, educational stipends, and healthcare allowances. However, such initiatives only offer short-term benefits to recipients and the economy. This underscores the urgent need for a concrete long-term plan.

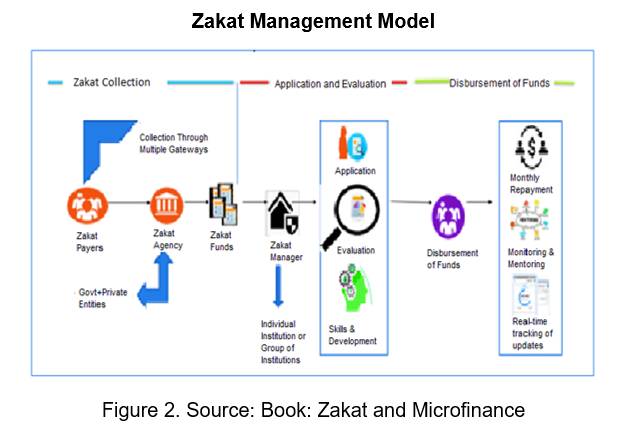

As Dr. Hussain Qadri proposed, the figure above presents a seemingly feasible model for Zakat to alleviate Pakistan’s poverty. Despite being a comprehensive way forward for the Zakat System, it lacks sustainability. However, another prominent model is the Fauji Foundation, one of the most successful models in Pakistan. It has created employment opportunities and provided financial stability to its beneficiaries, aligning with the objectives of Zakat. These models, when integrated, can form a sustainable Zakat system in Pakistan, instilling confidence in the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed recommendations.

Both models can be integrated to achieve a sustainable Zakat system in Pakistan. Therefore, it is imperative for all stakeholders, including the audience, to support the establishment of a National Welfare Foundation (NWF) using capital collected through Zakat. For centralised Zakat collection, funds from Zakat payers and private entities should be credited to the foundation, which invests in profitable sectors. Informal collection should also be integrated into this centralised system. Revenue generated from investments can be divided into non-refundable and refundable funds. Non-refundable funds should sustain institutions in education, food, shelter, healthcare, skill development, nursing homes, and madrassas nationwide, which has also been affirmed by Islamic jurists. Madrassa students may also be equipped with skills alongside religious studies for integration into the job market.

The refundable revenue will fund interest-free loans for small-scale businesses and enterprises, which will be repaid to the centralised fund in easy instalments and reinvested. This should be aligned with Islamic Banking practices, where banks can be integrated into the recollection of funds. This cycle will operate year-round for continuous support. Technology integration and Shariah compliance will ensure transparency and accountability, providing a sense of reassurance and confidence in the system. The digitisation of the system will maximise efficiency. Redirecting funds from Financial Support to Poverty Alleviation Programmes can create a sustainable impact.

This model may encounter concerns from different fiqh perspectives. Therefore, the government should facilitate an Ijtihad among moderate ulema from all schools of thought to reach a consensus, enabling the implementation of the model to help turn Zakat recipients into Zakat payers.

Hence, establishing NWF can help establish a robust system of collecting and distributing Zakat and achieve its true essence: poverty alleviation and social well-being. While Zakat is obligatory in Islam, its effectiveness entirely hinges upon adhering to Shariah principles and addressing the challenges.