The following article was initially published in a widely-circulated English daily of Pakistan, who subsequently removed it from their website for unspecified reasons. It is being published here with permission of the author.

Expose: Pakistan’s lame, apathetic foreign service

“The arrow shot by the archer may or may not kill a single person. But stratagems devised by a wise man can kill even babies in the womb.” ― Chanakya Kautilya

Long before Narendra Modi took over, India chalked out a comprehensive plan to marginalise and defame Pakistan, globally. Islamabad’s incompetent political leaders, rash generals and lousy bureaucrats unknowingly contributed their fair share. Yes, it sounds disturbing and even melodramatic. But it’s true.

After the Indian military took one month to mobilise along the border with Pakistan following the attack on the Parliament, the then Vajpayee-led government sought a standardised plan against Pakistan. The doctrine that resulted is called the Cold Start.

Besides, various localised thrust of military hardware aimed at inflicting damage to the adversary and eventually disabling the use of a nuclear option, it assigned equal significance to the government’s diplomatic arm – the external affairs ministry – to portray Pakistan as the ‘epicentre of terrorism’. The Indian media, which rarely challenges the South Block, built the narrative which the Indian diplomats efficiently propagated through official and unofficial channels.

Meanwhile, Islamabad basked in the narcissism of (retd) General Pervez Musharraf with his political opposition treating its wounds in Jeddah and London.

Sartaj Aziz urges foreign envoys to pursue proactive diplomacy

So now, India has taken off both its gloves and mask. The war drums are beating with chorus of Hindutva militia at full pitch.

“War is the continuation of politics by other means,” said Carl Von Clausewitz, the legendary military theorist. India’s policy used in the past will be maintained by war or war mongering. The Pakistani military might be ready and armed-to-teeth but there is one huge gap in its defenses: the lousy foreign ministry and its venal diplomats.

After over two-dozen background interviews, this correspondent has been able to synthesise some of the core flaws, confronting efficiency of Pakistan’s foreign ministry.

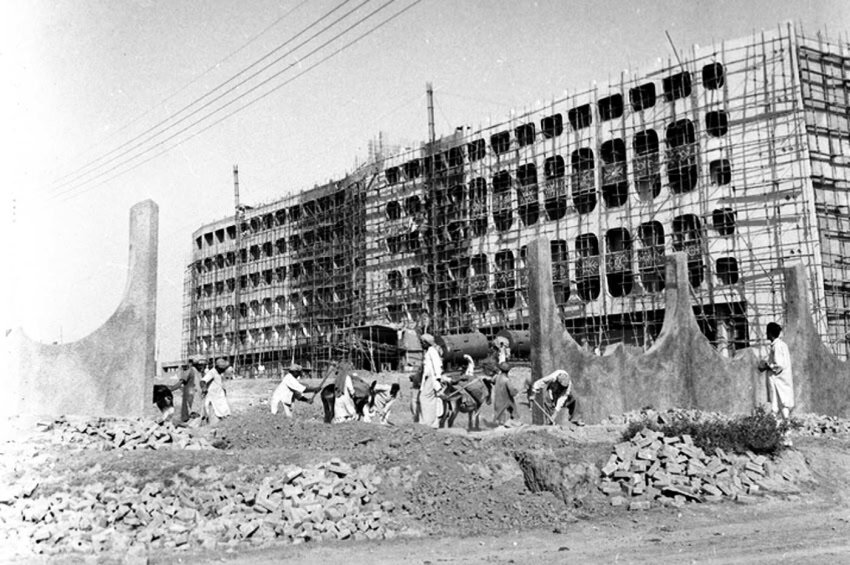

Being the second largest Muslim country and sixth most populous nation, Pakistan has significant diplomatic footprint in the world. The number of embassies has grown and so has the staff deputed there. Over the past three decades, however, the country’s civil services have steadily declined in terms of quality of manpower, training and motivation. This may have a lot to do with politicisation of bureaucracy as well as military’s soaring interference.

Currently, the ambassadors appointed can be divided in three categories: career diplomats, retired military officers, ranging from colonels to generals, and political appointees including mid-level bankers, such as those in Qatar, to top-notch journalists like Dr Maleeha Lodhi. The mix baggage brings out mixed results. Not all career diplomats know what they are supposed to do, while not every political appointee or ex-military man is there to enjoy the perks.

There is little or no communication between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other institutions of national security and internal security of Pakistan. One example is that of Pakistan’s policy on drone strikes. While the Ministry of Foreign Affairs printed reams of paper on Pakistan’s anger and protests on drone strikes, the United States’ CIA and Pakistan’s military were both cooperating on drone strikes and targeting of alleged militants.

Brainstorming at any level is non-existent in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The additional secretaries’ meeting is the only forum in the ministry where some sort of minimal discussion or say brainstorming takes place. However, this is only at the highest level and does not engage even director or other top level officers. From the additional secretary level to the assistant director, 99% of the effort consists of writing inane and clichéd talking points and worthless notings on irrelevant files. They are precisely glorified clerks, mostly playing the role of postmen.

The result is that foreign policy is made mostly on whim and dictation from either the General Headquarters or the Prime Minister’s office, leading to U-turns and last-minute firefighting. A case in point can be the Torkham border-crossing row with Afghanistan, the Foreign Office was unaware of the discussions between the army and the Afghan ambassador.

Despite major back-to-back challenges such as Indian nuclear tests in 1998, followed by September 11 attacks, the Pakistani foreign ministry could not establish a round-the-clock crisis centre. Pakistani embassies in Mexico or Argentina have to comply with Islamabad’s office timing in case a diplomat brother has to reach out to the headquarter on some important matter. How many countries in a similar situation can rely on a 9am to 3pm standard office routine?

With career planning virtually non-existent, there is no co-relation between language training and foreign posting. In many cases, officers are never sent to the country whose language they have learnt, thus they lose the ability to either speak or write in it.

While there is no foreign policy evolution process at work, there is no regional, bilateral or multi-lateral specialisation. An officer serving in New Delhi might be posted to Pretoria in South Africa. Eventually most Pakistani diplomats remain amateurs with very basic skills of knowing how to wear a tie and a suit and locking themselves up in embassies or consulates.

Pakistan, a country that is involved in major legal disputes, has the weakest expertise in international law. These ramshackle offices with two or three officers are a sick pretension of the international law capacity in the ministry, thus leading to an outsourcing of cases for Pakistan’s defence to legal fraternity in the private sector. Obviously, no lessons were learnt from the drowning of Pakistan Navy’s spy plane by India or failure to win litigation on water conflict. There are bound to be more legal issues with India, owing to her admission to larger number of critical multilateral forums and Afghanistan toeing its lines.

The Indian embassies, on the contrary, maintain better quality of service with particular emphasis on public policy and community engagement or service. The media narrative, which already is damaging to Pakistan, is further supplemented by the Indian journalists working in foreign countries, such as the Gulf region and North America. While the state largely controls the media in the GCC region, the English language newspapers are flooded with anti-Pakistan headlines while nothing critical can be published against the ruler of another friendly country, such as Egypt’s Sisi regime.

For Pakistan there is also total inability of writing anything beyond ill-composed letters to the editor. Op-ed articles by Pakistani diplomats are unimaginable and media monitoring at embassy-level is negligible, as most diplomats take the press coverage as fait accompli.

While one of the primary tasks of embassies is consular service, there is absolutely no training of foreign service officers in such matters. In fact the quintessential training of a Pakistani diplomat is antithetical to compassion, kindness and empathy needed for consular work. Such traits are never sought after in an officer when posting to consular missions, catering to large Pakistan expatriates. There are exceptions of some extremely capable consular officers, but very rare!

Though they join the service after passing Central Superior Services’ examination, 60% to 70% of Pakistani diplomats cannot speak simple English while addressing audiences in universities and think tanks. Blame the quota system if you will or the foreign ministry itself, which lacks anything but discipline and focus. Even in cases where they do speak, the diplomats are totally bereft of intellectual depth or the ability to speak beyond clichéd, hackneyed briefs which are of zero interest to well-informed audiences in Europe and North America.

One case in point was the total lack of response to the poisonous anti-Pakistan narrative spun out of Toronto by Tariq Fateh and his gang of half a dozen followers. Their connections for funding such narrative are abundantly well-known. Over the last decade, nobody amongst the Pakistani diplomats in prized stations such as Washington DC, New York, Los Angeles and Toronto invested enough effort and intellectual depth to counter shallow and venomous narratives of Fateh’s ilk. It was only the individual effort or unofficial audacity of a diplomat and some expatriate Pakistanis in Canada who demolished the claims. Majority of Pakistani diplomats are devoid of such calibre, motivation and absolute knowledge of history and affairs.

In the age of alternate media, tragically, Pakistani diplomats are utterly untrained in using social media for foreign policy objectives. So far, Ministry of Foreign Affairs has not held a single workshop on the use of social media, whereas such trainings are held routinely in small, private sector organisations. Therefore, lack of resources cannot be an excuse for lack of vision and total ignorance from advancement in communication.

Embassy websites are another fiasco. Lacking a standardised format, the information provided is rarely updated and most insufficient to answer basic questions. Top foreign ministry officials along with the ones posted in embassies rely on Gmail, Hotmail or Yahoo for official communication. Facebook pages and Twitter handles of ambassadors and embassies are non-existent, and those having accounts are not active. WhatsApp and Viber provide the best hotlines.

The foreign ministry direly necessitates massive restructuring and reforms. The government needs to debate as to whether it must take officers from the CSP pool or those who appear and pass through rigorous evaluation processes specifically evolved for the country’s future diplomats. Should diplomats be attending the courses for promotion with other bureaucrats of grade 19 and beyond? The question of promotion criteria is equally crucial. Should not their specialisation, dedication, analytical skills and foreign language proficiency form the criteria? Ominous is the acute dearth of analytical skills in diplomatic corps employed by Islamabad, given fast-paced developments, realignments in the region and the world, as well as conflict deepening or emerging.

To a significant extent, apathy towards Foreign Service academy is to be blamed as well. From communication skills to the art of negotiation, the training leaves a lot to be desired. The stiff-necked young officers it churns out are too lightweight to keep up the traditions of Sir Zafarullah Khan, Pitras Bokhari, and Sahibzada Yaqub Khan et al. The academy should not only be the focal point for training but also career planning and specialised and advanced courses.

Non-diplomatic staff is another thorn in the neck. They are no different in aspiration and selfish pursuits than the ambassador and other diplomatic staff. Lacking proper training, devoid of local language and charmed by facilities abroad, often such clerks and secretaries act like ambassadors within community and mint money in return for their assigned jobs.

To forward Pakistan’s national interest and to counter India’s Cold Start doctrine, the foreign ministry can’t be left in the cold. If ambassador Tariq Fatemi is not abreast of the flaws and ready to reform, who else would!