By: Ms Rafia Ashar

Fundamentally, countries rely on three channels to earn foreign exchange; foreign direct investment (FDI), exports, and remittances. Among these, remittances play a significant role for developing nations like Pakistan, where the export of skilled and unskilled labour to international markets has become a key driver of economic growth. This insight will focus on the aspect of remittance flows through manpower export from Pakistan.

Ministry of Overseas Pakistanis and Human Resource Development (MOPHRD) plays a central role in facilitating labour migration and ensuring the welfare of overseas Pakistanis and their families. To streamline and regulate manpower exports, the ministry supervises key institutions, including the Bureau of Emigration and Overseas Employment (BE&OE), the Overseas Pakistanis Foundation (OPF), and the Overseas Employment Corporation (OEC).

In 2020, MOPHRD formulated the latest National Emigration & Welfare Policy for Overseas Pakistanis, which established a structured approach to labour migration. Prior to this, labour migration was primarily facilitated by the Migrant Resource Centre (MRC), which focused mainly on deploying workers to Gulf countries, alongside private recruitment agencies that lacked a proactive policy.

The latest policy interconnects the BE&OE, OPF, and OEC to ensure a coordinated effort in overseas employment. Pakistan regulates the emigration of its workforce for overseas employment through the 1979 Emigration Ordinance, administered by the BEOE. The 1979 Emigration Rules and Regulations outline multiple pathways for Pakistanis to secure employment abroad. Workers can either obtain jobs through an Overseas Employment Promoter (OEP), which may be public or private through personal efforts (direct employment), or with the assistance of already employed overseas.

BEOE plays a key regulatory role as it is responsible for issuing licenses to private OEPs, monitoring their activities, and ensuring compliance with labour laws to safeguard migrant workers. As of February 2025, a total of 2,697 active licensed OEPs are registered with the Protector of Emigrants Offices, which oversee the legal clearance of departing workers. For government-facilitated employment, the Overseas Employment Corporation (OEC) serves as the official manpower-exporting agency, primarily handling foreign government requests for Pakistani workers.

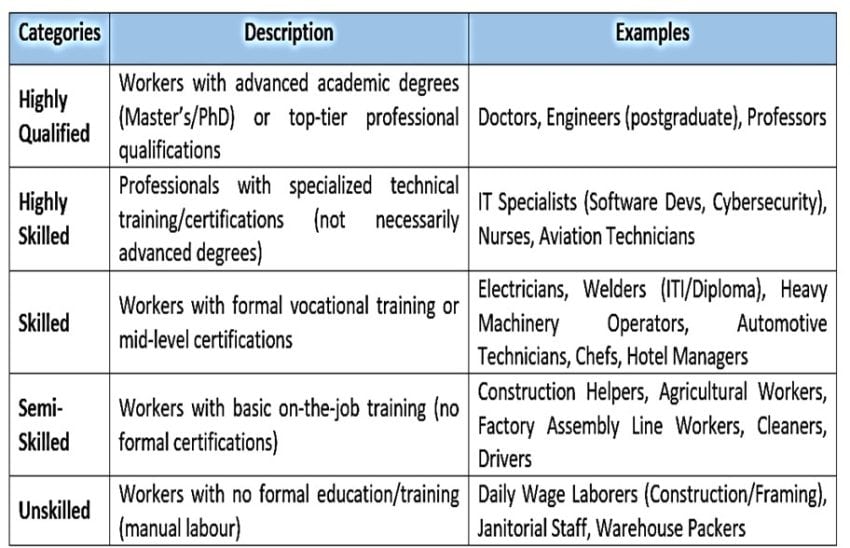

Ministry categorises overseas workers into five distinct groups; as shown in the table below depending on their level of education, vocational training, and professional certifications.

Based on these Classifications, the following graph shows the export of manpower over the last 05 years.

Figure 1

Source: BE&OE

The graph highlights fluctuations in manpower exports, with a steady increase in labour exports from 2020, peaking in 2022 & 2023, with unskilled and skilled workers making up the largest share, but it also indicates a sharp decline in 2025. However, the region wise supply of manpower indicates that the Middle Eastern region has been the

| The decline in Pakistan’s labour export model stems from outdated vocational trainings, lack of diversified markets, and a persistent overdependence on traditional Gulf region. |

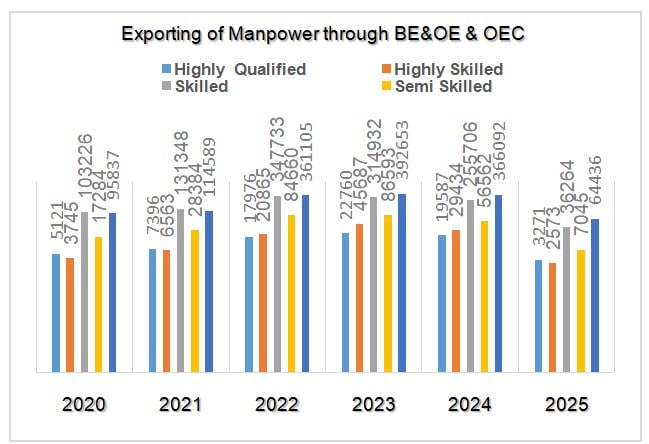

Top destination for Pakistani manpower, with KSA absorbing the highest number. While Middle Eastern nations continue to be the primary labour markets, migration to non-traditional markets in Europe, Africa, and East Asia remains marginal as shown in the graph below.

Figure 2

Source: BE&OE

The supply of manpower remained relatively high throughout 2024 after COVID, driven by several key factors. Notably, the government launched awareness programs aimed at encouraging labour deployment beyond the traditional Gulf markets. Additionally, the introduction of the Overseas Portal, a centralized, government-run platform; marked a significant improvement over the previously fragmented and disjointed online systems. This digital integration streamlined access to information and services for prospective migrant workers.

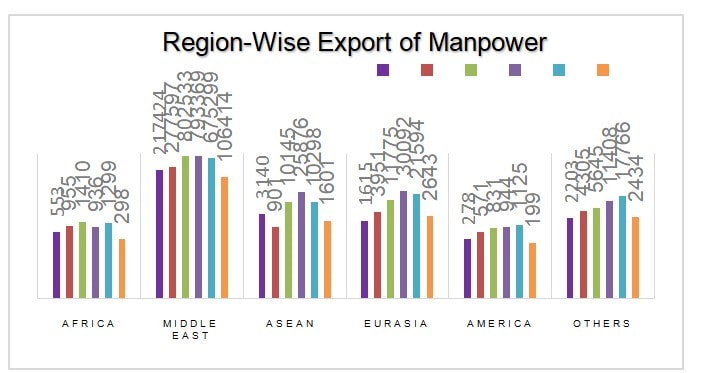

However, the decline in labour supply during 2025 is mirrored in remittance inflows, with the graph showing a peak in 2024. It also highlights that contributions from regions beyond the Gulf and the EU remain minimal.

Figure 3

Source: SBP

The graph depicts that Pakistan receives the highest remittances from the Middle East (Notably from KSA, U.A.E) driven by a larger concentration of migrant labour in the region. The State Bank of Pakistan in a press release reported ‘’Saudi Arabia as a top contributor as Pakistan remittances grow 38.6% and 3.8% on year-on-year and month-on-month basis’’. In contrast, other regions contribute relatively modest amounts, both in aggregate and on a per worker basis.

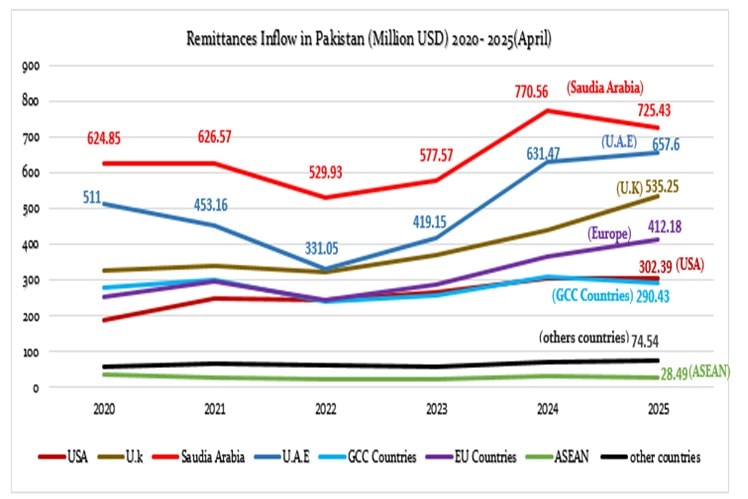

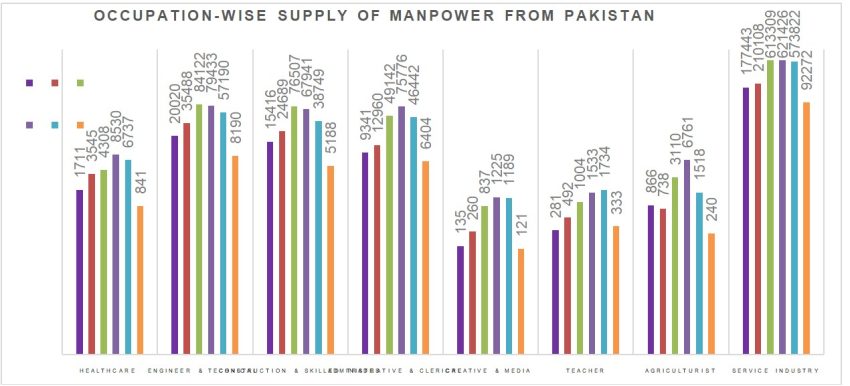

The majority of this workforce falls into the labourer category, with a significant portion being unskilled and lacking formal training. The following graph reflects that the service Industry (Notably labourers& Drivers) has the highest supply over all.

Figure 4

Source: BE&OE

The above data highlights that majority of workers deployed abroad from Pakistan fall into the unskilled labour. It also indicates the lack of diversification in skilled professions, limiting the country’s ability to compete in the global job market. In addition, the government asserts a disparity between the supply and demand of labour as in 2022, inefficiencies and the absence of a structured policy framework for human resource exports led to a backlog of 116,826 vacant job positions, some dating back to 2021.

Pakistan’s labour export framework is marked by a divide between the process of human resource development (HRD) and human resource management (HRM). Technical institutions like NAVTTC (National Vocational and Technical Training Commission) and TEVTA (Technical Education and Vocational Training Authority) are primarily responsible for HRD and conversely, MOPHRD oversees the management and deployment of this workforce abroad. At the federal level, the Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training (MOFEPT) sets broader policies and strategies while the NAVTTC acts as a regulatory body. In provinces, TEVTA is responsible for implementing these policies. Pakistan has 3,740 technical institutions, of which 56% are private and 44% are public.

It raises critical questions on the efficacy of technical institutes particularly regarding the relevance, alignment and quality of their training programs but also exposes a lack of coordination and foresight on the part of the Ministry in articulating foreign labour market demands to these training bodies. This points to a lack of an integrated approach between the ministry and the training bodies whether in identifying market needs or in designing and delivering targeted skill development programs.

Moreover, another pressing challenge is the malpractice of OEPs, who often misrepresent unskilled workers as skilled to secure foreign placements and extract higher fees. This deceptive practice not only exposes workers to exploitation and job insecurity abroad but also damage Pakistan’s credibility in global labour markets. Incidents of workers going missing or becoming undocumented further highlight the gravity of the issue. For e.g, In April-May 2024, Europol exposed a network of Romanian and Pakistani nationals falsifying work permit applications, obtaining 102 through OEPs or fake consultancies in Pakistan. Around 76 reached Western Europe, while 26 were caught in Romania, Italy, or Austria. Several Pakistani migrants went missing after arriving, becoming untraceable as they left legal routes and lost contact. In April 2025, FIA arrested 3 agents involved in visa fraud schemes targeting individuals seeking employment in Romania. One victim was deceived into paying nearly PKR 1.95 million for a job offer that never existed, arranged through a fake OEP/ consultancy firm.

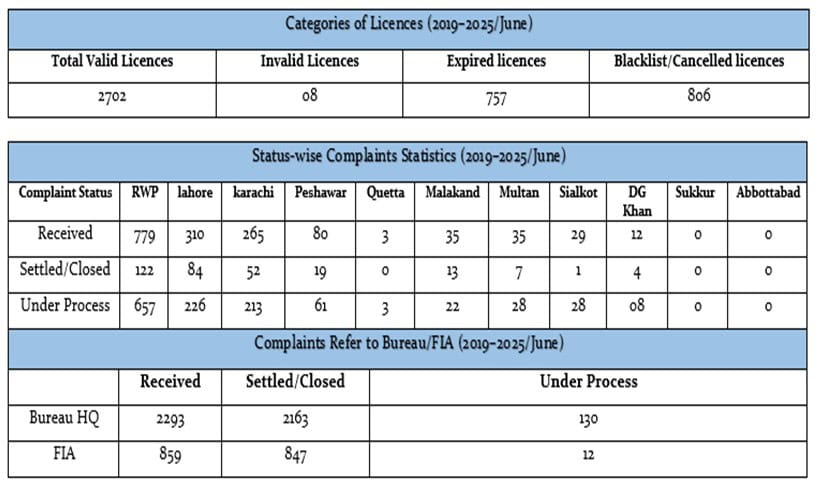

The following table highlights the blacklist licences of OEP by BE&OE and complaints received against them.

Figure 5

Source: BE&OE

The data reflect the persistent regulatory weaknesses in overseeing OEPs. Although a large number of licences remain active, a considerable share has either lapsed, been blacklisted due to serious violations. On the complaint front, the figures reveal alarming inefficiencies; a substantial backlog of unresolved or pending cases, many of which have escalated to higher authorities or entered legal proceedings. This pattern highlights the critical gaps in enforcement, accountability, and institutional responsiveness.

Several concerns have also emerged over governance and financial irregularities within MOPHRD, as well as technical institutions. Investigative reports have highlighted case s of embezzlement and mismanagement. Similarly, NAVTTC has raised concerns about unregistered bodies issuing counterfeit certifications, undermining the credibility of technical and vocational training in the country. Transparency International Pakistan also pointed out the MOPHRD violations of public procurement rules, emphasizing lapses in transparency and accountability.

The National Assembly Standing Committee on MOPHRD also expressed dissatisfaction over the ministry’s inadequate implementation of anti-corruption measures, highlighting persistent issues in its subordinate departments.

In nutshell, despite ongoing reforms & pro-emigration policy, Pakistan’s labourexport remains disproportionately concentrated in the Middle East, with only minimal progress in tapping into alternative markets. This also reflects a deeper policy disconnect as technical institutes lacks the capacity to deliver quality, market-relevant training, while ministries failed to secure diversified demand or coordinate effectively. Such disconnect has also indirectly drives illegal migration; a challenge that could be significantly reduced through coherent and well-integrated labour export framework. Without a targeted structural approach, Pakistan’s labour export strategy risks stagnation.

Email: rafiaashar.413@gmail.com