US President Donald Trump, his French counterpart Emmanuel Macron and British Prime Minister Teresa May have agreed to take punitive actions against Bashar al-Assad for repeatedly using chemical weapons. Last night, China abstained from voting in both resolutions, the first by the US and the second by Russia. Around the same time, the European aviation watchdog advised commercial aviators to clear the Syrian airspace and a chunk of the eastern Mediterranean Sea too. Unlike former US President Barack Hussain Obama, his successor Donald Trump wants to make good on his promise of taking action against Assad whenever he used chemical weapons. Now three members of the UN Security Council favor attacking Assad and denying his ability to use WMD’s again, China opts to stay neutral for a possible mediatory role, and Russia continues to back Assad.

The attack on Assad’s military asset, and possibly his own life, seems imminent. The situation here is far different from US President Bush’s attack on Saddam’s Iraq. Unlike Saddam, Assad has committed crimes against humanity by repeatedly using chemical weapons against civilians. UN reports are a testament to his fetish for the mass cruelty that continues. More than half of the Syrian population has either fled the country or has become homeless on their own. Besides, over half a million have died while there are no reliable statistics for those injured and jailed.

Should the world sit and watch as a powerful ruler crushes his defiant countrymen? A casual and popular answer would be a yes. However, since WWII, the global norms for the protection of the civilian and the human rights have improved considerably.

The war crimes and crimes against humanity in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda led the United Nations to start an initiative called the “responsibility to protect” (R2P). In a departure from the standard principles of international relations concerning the protection of national frontiers, the new idea promoted the concept of sovereignty being, not a right of a state, but its responsibility. So, when a regime commits war crimes and crimes against humanity, it fails in fulfilling its responsibility towards sovereignty, giving the international community the right to take necessary measures for the protection of civilians and deter continuation of abuse.

For a layman, the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) is a global political commitment, which was endorsed by all member states of the United Nations at the 2005 World Summit to prevent genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

The fire in the olive garden

Since Syrians stood up against the Assad family after four decades of tyranny in 2011, the regime has been responding with zero tolerance toward dissent. Within weeks, dozens of protestors were dead, but the urge for self-respect was only increasing. After protestors were attacked by the armed forces, self-respecting officers and soldiers started refusing such orders, thus creating a robust opposition force later called, the Free Syrian Army. Then began an armed confrontation, eventually turning into a civil war.

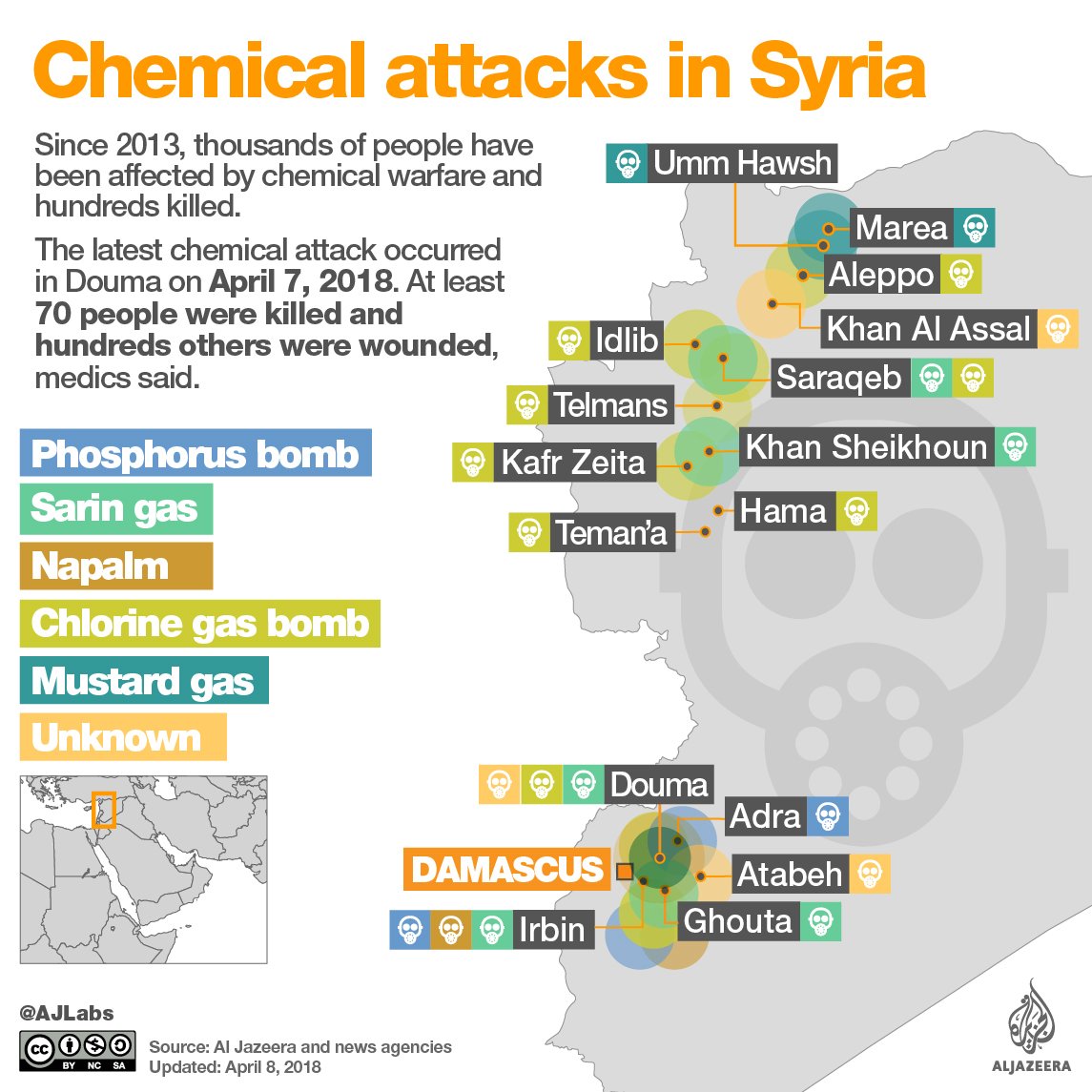

Barring a single forewarned and symbolic US cruise missile attack on a Syrian base in 2017, the principle has not been applied against Assad in its true sense. The minority-led pro-Iran regime has resorted to indiscriminate aerial bombardment and extensive use of chemical weapons in rebel-held areas with significant civilian population, which either chose to stay put or could not afford to travel to a refugee camp in a foreign land.

By all means, the world community – UN member-states – must invoke the principle of the responsibility to protect. To understand the impending attack on Assad’s military, the evolution of the Syrian crisis should be viewed from the perspective of R2P. The policies of key global actors which attempted to intervene in the situations, such as the P-5 (the veto-powered UNSC members) and League of Arab States, have evolved from the non-interventionist approach to a more pronounced and pro-active confrontation.

The Syrian crisis involves multiple, serious problems that undermine the importance of the R2P principle in international relations and international law. The use of force to effect regime change in Libya and Côte d’Ivoire also undermined the UN taking effective action in Syria.

Various landmark events in the Syrian uprising occurred as it transited from protests to civil war and eventually the multilateral diplomacy resulting in disarming Damascus of its Weapons of Mass Destruction, precisely by its readiness to comply with Chemical Weapons’ Convention, rise and fall of ISIS and reintroduction of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime.

Stark realities of realpolitik are that the UN member-states make little and half-baked attempts to articulate the case of responsibility to protect. This Syrian crisis has so far highlighted the controversy as to whether a state can use force for humanitarian purposes without Security Council authorization, a long-standing international legal question that did not arise in the Darfur, Libya, or Côte d’Ivoire crises.

The rationale of some member states, which considered the Syrian crisis an internal matter, became absurd when violence in the country began to creep across the borders into Turkey.

Like now, the UK did come very close to enforce the R2P principle but shied away because of geopolitical considerations and lack of support by the Obama administration. Trump’s predecessor wanted to avoid expanding the US military footprint in a cold-blooded manner, thus creating vital geopolitical opportunities for Russia. In normal circumstances, a key consideration for nation-states must be the civilian protection, instead of geo-strategic or geopolitical interests. Undeniably, the United Nations is based on the idea of a global consciousness, which should react to injustice and speak effectively through its institutions such as Commission on Human Rights, General Assembly and Security Council. The actual events on the ground highlight the difference between concept and reality.

Sovereignty: Right or responsibility

The international community has not only consistently and apathetically ignored prevention of mass atrocities in Syria but has also failed to take action to suppress the offenders. Given the politics that has characterized the Syrian crisis to date, the likelihood of effective international cooperation on rebuilding Syria is also bleak. Even within the Muslim countries, the public outcry on Syria has been shamefully non-existent.

Turkey also acted reluctantly due to NATO and the Obama government’s lousy approach to the Middle East. On the contrary, Iran and Russia teamed up not only to save Assad’s regime but also to quell dissent.

The joint military action in Syria revives the tension the world withstood during the Cold War. Russia has warned the US outright against firing missiles at Syrian bases, threatening to intercept them and retaliate against the launching platforms i.e. aircraft carriers, submarines and warships etc. Russian military muscle is inferior to its rivals, thus the operation can be marginally impacted. The Kremlin won’t let Assad go or weaken its grip on Syria which it controls like a colony.

China’s neutrality can offer some relief. Its mediatory efforts can result in a resolution leading to the formation of a board based UN WMD inspectors, which Russia has opposed tooth and nail while denying any use of chemical weapons in Ghouta. Germany, another important power in Europe and NATO, has been observing the developments from the fence with keen interest. Beijing and Berlin may work together to calm down the situation in Syria.

The convention of R2P has become more vividly pronounced than ever before. However, the other noteworthy development is the fracturing of NATO on the question of R2P in Syria. And finally, China has not opposed it though it maintains a strict policy of lack of intervention in the state’s internal affairs. Lastly, either way – if the allies strike against Assad or diplomacy prevails and a new UNSC resolution is passed – the future role of Russia in Assad’s Syria won’t be a walk in the park. Putin has seen Turkey’s Erdogan and Iraq’s Maliki siding with the US against Assad.