By Khanzada Bilal

Disputes in the South China Sea (SCS) have gained significant attention due to the ongoing rivalry between the United States (US) and China. The US aims to contain Beijing’s rise as a near-peer, and its containment strategy is intensifying competition in the Asia-Pacific region, particularly in the SCS. This insight explores the current geostrategic dynamics of the SCS, emphasising the significance of its geography, the historical context of the issues at hand, and the escalating strategic competition in the region.

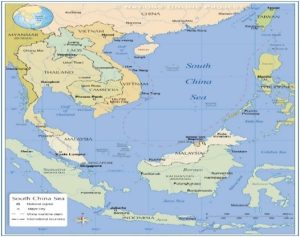

The SCS covers around 3.5 million square kilometres, borders China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, and the Philippines, and provides a significant maritime corridor for global trade. Approximately 30% of global maritime trade, including oil, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and consumer goods, passes through this. It links the Strait of Malacca (to the West) and the Taiwan Strait (to the East), making it a crucial passage for East Asian economies—about 60% of China’s trade and 80% of its energy imports transit through the SCS. At the same time, the US, Japan, South Korea, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries depend on the SCS for trade and supply chain security.

Chinese dynasties, Southeast Asian kingdoms, and European colonial powers navigated the SCS for trade and territorial control for ages without significant disputes. It became disputed in the wake of the Japanese defeat at the hands of the US during World War II, creating a power vacuum once Tokyo was forced to surrender the territories under its control. Surrounding states made competing claims for islands and reefs, citing precedents, colonial treaties, and geographic proximity to assert their rights.

Political Map of the South China Sea

Source: nationsonline.org

Territorial disputes between littoral states brewed in the 1970s, eventually boiling into clashes for fishing rights and natural resources. The discovery of substantial oil and gas reserves further exacerbated tensions. The disputes extended to control over islands, shoals, banks, reefs, and other features spreading across the SCS. For instance, although small in size and uninhabited, the islands called Paracel and Spratly by the US-led West and Japan, and Xīshā Qúndǎo and Nánshā Qúndǎo by China, are bone of contention for two main reasons: who owns them to apply the rules, and what can be done in the surrounding waters?

By the 1980s, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Vietnam started establishing a presence on various islands and reefs. The naval skirmish between China and Vietnam in 1988 at Johnson Reef marked a significant escalation of territorial disputes in the region, compelling China to assert its claims.

China, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Taiwan occupy around 70 disputed reefs and islands in the SCS, with over 90 outposts. According to Western reports, China has twenty outposts in Paracel and seven in the Spratly Islands. In Spratly only, Malaysia has five features, the Philippines controls nine, and Taiwan has one. Vietnam maintains a presence on 49 – 51 outposts across twenty-seven features, and the status of two construction projects on Cornwallis South Reef is unclear.

In the past two decades, the SCS has become increasingly prominent, driven by China’s increasing economic power, focus on the blue water navy, and US-stated policies to contain China’s rise. As a non-littoral external player, maintaining ascendancy in the SCS is a geostrategic imperative for the US.

For China, this implies asserting the rights of free and open seas and the right of safe passage in its sea lines of communication (SLOCs). China noticed these forays into what it considers its territories and responded by initiating island-building efforts. Between 2013 and 2015, it asserted its rights by creating around 3,000 acres of artificial islands on coral reefs in the Spratly Isles.

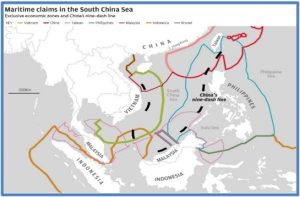

China also enacted maritime laws in 1992 as a signatory of the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to protect its maritime rights in the exclusive economic zones (EEZs). Though the US has not ratified UNCLOS, using sovereignty, economic and military concerns as excuses, it strongly supported the Hague Tribunal 2016 arbitration ruling, favouring the Philippines’ rejection of China’s Nine-dash Line claim.

Maritime Claims in the South China Sea

Source: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

China does not view its relations with the littoral states of SCS as a zero-sum game. It continues strengthening its relations with the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, and other nations involved in SCS disputes. China is also actively promoting consultations regarding the “Code of Conduct in the SCS” with the ASEAN.

For the US, engaging China’s neighbours and supporting them in keeping Beijing embroiled in a local mess of an increased cycle of militarisation and diplomatic tensions is strategically convenient. In its “Pivot to Asia” policy, re-named Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS) in February 2022, the US has committed to maintaining its post-1945 and 1991 hegemony. Its “rules-based order” now focuses more on countering China’s rise through alliances such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) between the US, Australia, Japan and India and the Australia-US-United Kingdom (AUKUS).

The US, its allies and partners sharply criticise China’s efforts to alter the status quo in the SCS, citing its so-called deepening military ties with Russia and North Korea as destabilising factors. In response, China highlights that these nations are inciting confrontation and distorting realities to hinder China’s development. At the Xiangshan Forum, a Chinese General placed the responsibility for rising tensions squarely on Washington, insisting that US intervention is the primary driver of instability.

Amidst these dynamics of the SCS, smaller littoral states walk on a tightrope and often prefer balancing their relations with the US and China. Conflict does not suit their long-term economic interests. However, hedging and maintaining a balanced foreign policy has significant military implications. Some of these states, like Indonesia, teeter on the edge and shy away from directly supporting potential US military operations in the SCS. Conversely, the Philippines has become more strident towards enhancing the US military’s ability to project power in SCS. The complexity poses a potential threat to the regional maritime security environment.

The SCS remains pivotal in the American struggle to contain China’s rise. This has intensified the economic and security challenges for the SCS’s littoral states. If the turmoil keeps increasing in the SCS, it will enhance the long-term importance of states like Myanmar, India, and Pakistan that provide direct access to the Indian Ocean Region if China is blocked in the SCS.