Locals in Minchanabad still believe the house was among the finest partition-era buildings of the city even when it was demolished few years ago with the purpose to build a modern accommodation in the tehsil of district Bahawalnagr of southern Punjab – some 44km west of Sulemanki headworks on River Sutlaj.

During the digging and construction work, Muhammad Khan found a unique treasure in a tin box buried under the old wall of the haveli. Finding it useless, the contractor permitted chief mason Khan to keep the tin box with him.

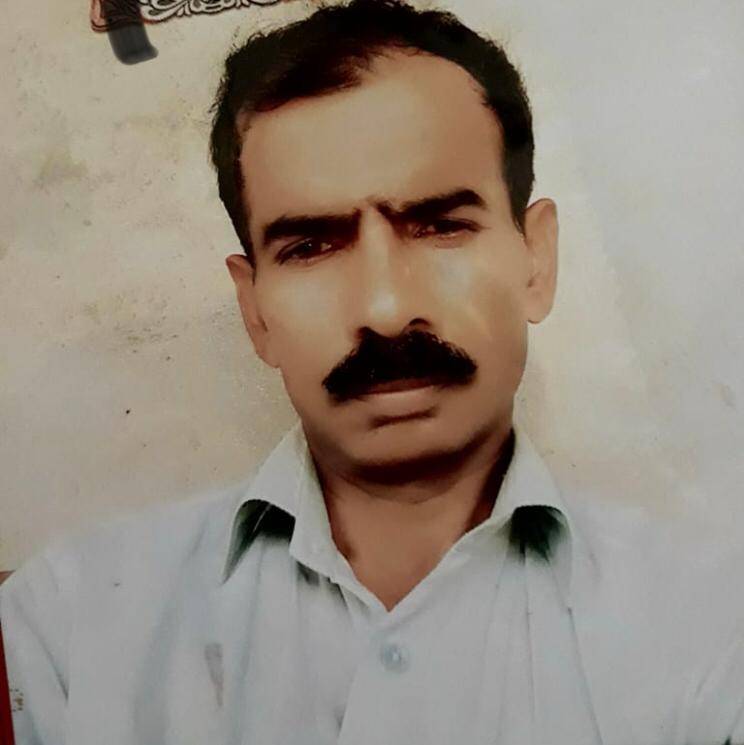

Resident of Behakan Bodla, a village two km east of Minchanabad, Muhammad Khan brings the tin box to his home and after few months, he gives it to Riaz Sidhu, a librarian and agriculture farmer of the same village. The ‘treasure’ inside the tin box was gramophone records, many of them already broken by Khan’s children.

Now in their early 50s, Riaz Sidhu and his younger brother Rafaqat Sidhu are great lovers of old Indo-Pak music. Play any song of Lata Mangeshkar, Muhammad Rafi, Kishore, Lal Chand Yamla, Surinder Kaur, Amar Sigh Chamkila, Kuldip Manak or any other top singer on YouTube, they will probably tell you everything about the track.

Their late grandfather Fateh Muhammad was from Dhanaula, a city of Punjab’s former princely state Nabha (13-gun salute state) which now falls in Barnala district of Indian Punjab. Sidhu Brothers say their forefathers had very good relations with Raja of Nabha, Hira Singh Sidhu (1843-1911), one of the rulers of Phulkian states (Nabha, Patiala, Jind, Malaudh) of pre-partition Punjab, and with Ripudaman Singh, the last raja of Nabha who was deposed by the British in 1928. A revolutionary soul, Ripudaman was a friend of Lala Lajpat Rai and other leaders of swaraj movement.

“Our grandfather owned a large haveli in Dhanaula. It was similar to the one demolished in Minchanabad,” said Rafaqat Sidhu while quoting the sad memories of partition he heard from his late father Rafique Sidhu.

“Our grandfather,” he continued, “donated a large piece of land to gurdwara in Dhanaula and to local Sufi shrine when my father born.”

However, despite being well-versed on the Indo-Pak history, Sidhus Brothers are unable to recognise the name of singers and melodies inscribed on the gramophone records they found in the ‘treasure’.

“Do you know these singers, have you heard these songs ever?” they asked while showing me the records when I went to meet them last month.

“Can you find the owners of these gramophones?

“We really wish to return these records to the family which built the haveli in Minchanabad and left it during the partition. We want to know about the person who had such great taste in music and did his best to save the records from being destroyed or stolen away,” they said.

Gramophone in the Subcontinent

Phonograph or gramophone, invented in 1877 by America’s greatest inventor Thomas Edison (February 11, 1847 – October 18, 1931), is also called record player since 1940s is a device for the mechanical recording and reproduction of sound.

The sound vibration waveforms are recorded as corresponding physical deviations of a spiral groove engraved, etched, incised, or impressed into the surface of a rotating cylinder or disc, called a “record” or gramophone/phonograph records.

The first voice of an Indian person was recorded by the Gramophone Company in 1899 in London, according to an article “Indian Gramophone Records -The First 100 Years” on a UK based website and scripts from the book “The Gramophone Company’s First Indian Recordings, 1899-1908” by Michael Kinnear,

In 1902, first gramophone disc was cut at Calcutta.

Until 1916, about 75 different record labels/brands were seen in Indian market, the important ones being – Nicole, Universal, Neophone, Elephone, H Bose, Beka, Kamla, Binapani, Royal, Ram-a-Phone (Ramagraph), James Opera, Singer, Sun, Odeon, and Pathe. With time, all these companies either disappeared or got merged with Gramophone Company. The name His Master’s Voice (HMV) and the label first appeared in 1916 and soon established their monopoly in the market.

During last one hundred years, over half million records were issued, spanning all musical styles in all Indian languages.

Gramophone Records in Minchanabad

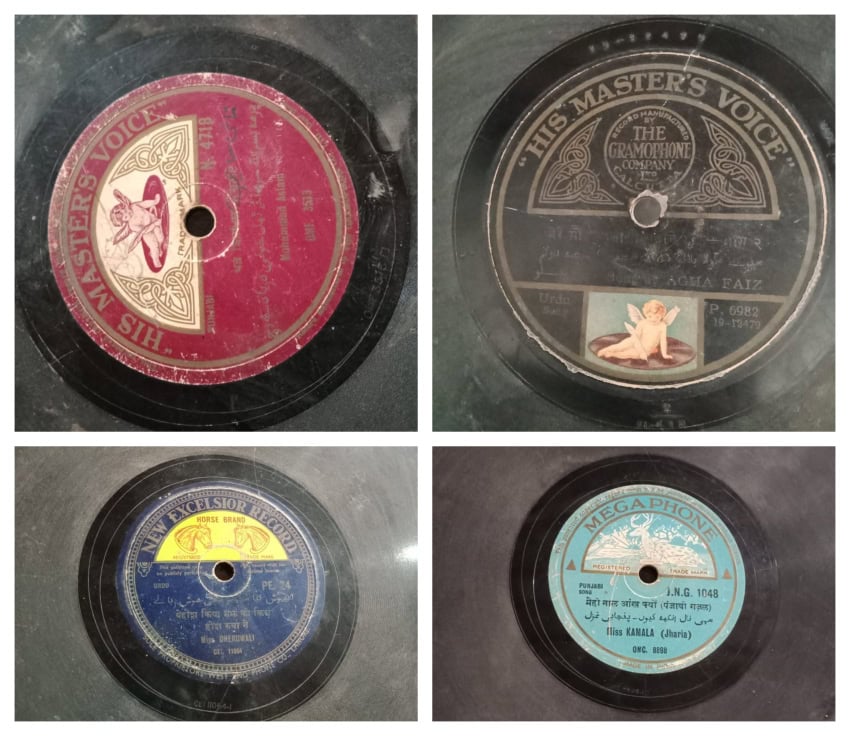

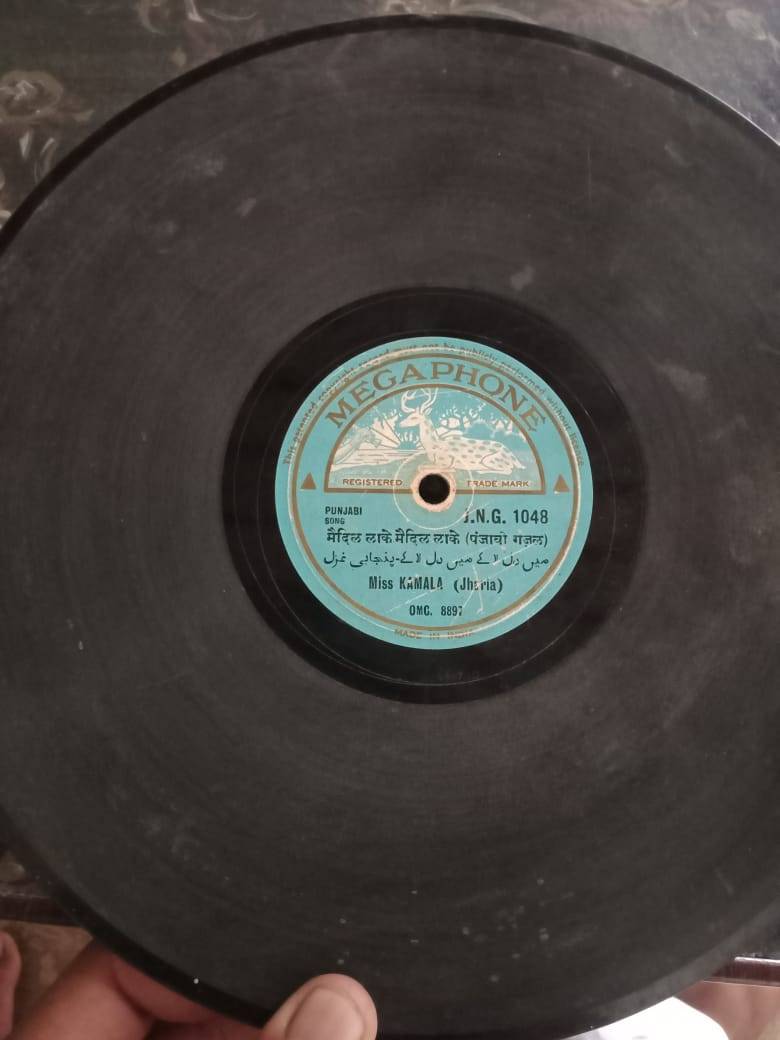

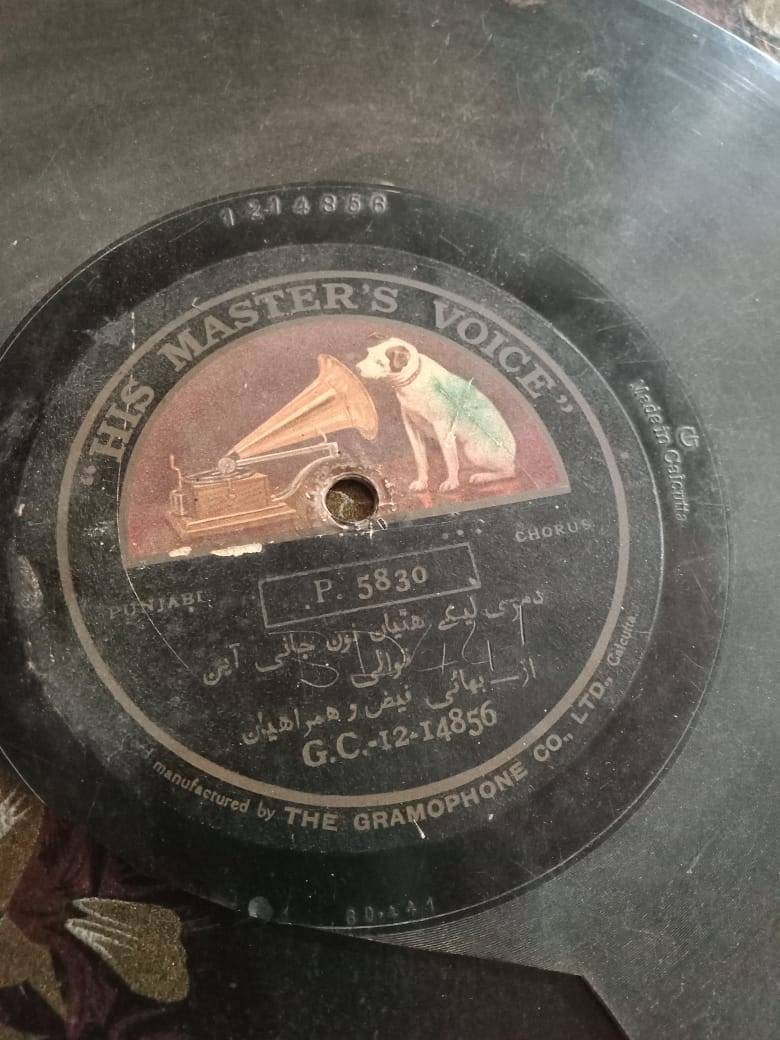

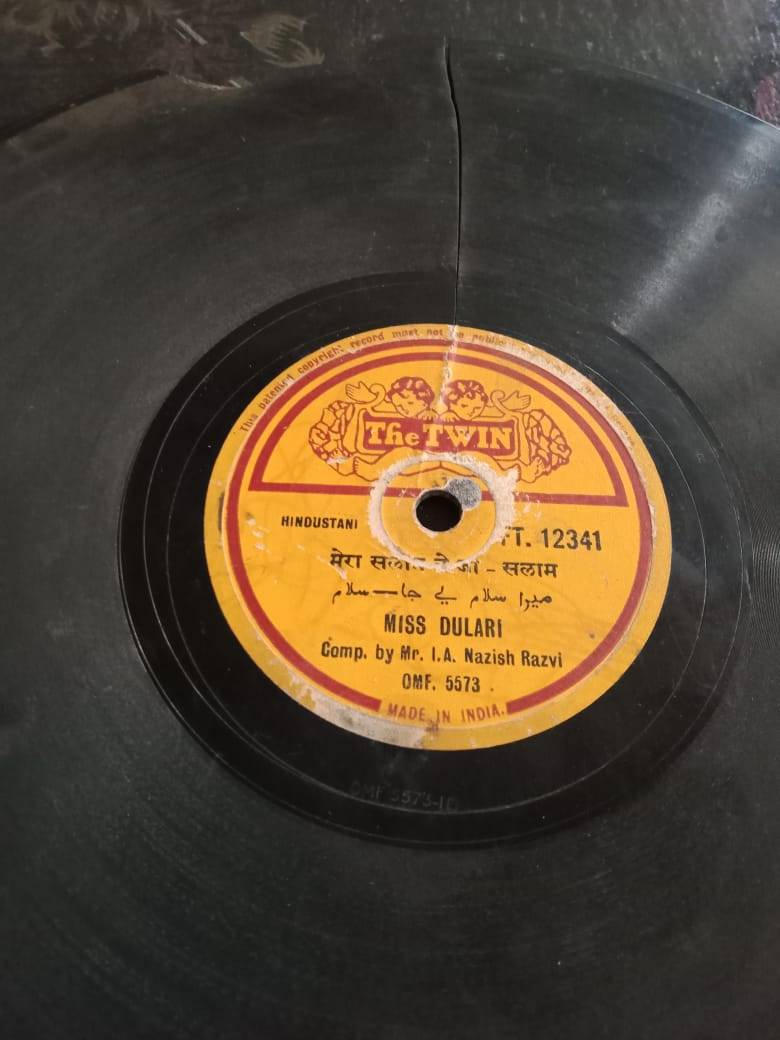

The records found under the old wall of a haveli in Minchanabad some years ago were of His Master’s Voice, New Excelsior Record and Megaphone companies.

One of them is titled “Parh Bismillah”, a qawwali by Mohammad Aslam. The other record inscribed with the name of Agha Faiz (also called Bhai Agha Faiz), a singer from Amritsar who was considered a very sophisticated folk and semi-classical vocalist of 1940s.

Another record bears the name of Inayat Bai Dheruwali, one of the earliest great melodies who recorded different compositions for Radio Lahore along with Ustad Barkat Ali Khan and Roshan Ara Begum before partition.

A song of Kamala Jharia, real name was Kamala Singha, is mentioned on one of the records found in Minchanabad haveli. Kamala lived in the palace of the Maharaja of Jharia (now in Dhanbad district, coal capital of India in Jharkhand state). Born in 1906 in Jharia, Kamala died on December 20, 1979 in Calcutta after making great contribution to Indo-Pak music.

A song by Miss Dulari, a Hindustani vocalist from Peshawar who specialised in several genres of classical music, inscribed on another records.

“Can you find the owners of these gramophone records?” Sidhus repeated his question and I shared with them the story of Marina Wheeler, the former wife of British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who made a journey from UK to Sargodha in a quest to find the remains of the house of her maternal family which fled from Sargodha to Delhi in 1947.

“Never speak about what we lost in partition,” this was precisely the advice of Marina’s Sikh grandfather to his children after they settled in Delhi.

But, for the love for music, Sidhus say they will keep telling people the stories of partition.