Pakistan’s foreign policy is largely Kashmir-centred and it takes a lot of pride for being the sole advocate of Kashmiri People’s right to self-determination. Pakistan has been supporting Kashmiri insurgent groups for decades, it has condemned Indian forces for suppressing ‘Pro-Pakistan’ movements through lethal means.

But sadly, Pakistan is not interested in recognising and supporting the rest of the Kashmiri movements and people that do not necessarily endorse Pakistani state’s narrative regarding Kashmir and India.

After the death of Burhan Wani, Pakistan has been trying to win the case it lost long ago; Kashmir’s annexation with Pakistan.

One example of these double standards is Maqbool Butt. A Kashmiri separatist and co-founder of Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front who was hanged on February 11, 1984 by the Indian government on the charges of killing an Indian intelligence officer. He posed serious threats to Indian administration and apparently confirmed with Pakistan’s official anti-India rhetoric.

But why we never glorified him? We don’t even hear about him. The reason is that he did not uphold the Pakistani official narrative on Kashmir. Maqbool was against the ‘Occupation’ of both the states. He claimed to have represented the majority of Kashmiri population and he also succeeded in gaining significant popularity and support. Maqbool butt was also an ambigious personality, not deemed as useful tool, both Pakistan and India declared him agent and spy of their rivalries. In India he was declared a Pakistani agent and in Pakistan he was arrested. His words in court Pakistani court were:

“Freedom and independence is the fate and destination of Jammu Kashmir. Indian rulers or Pakistani generals and bureaucrats cannot enslave Jammu Kashmir for a long time.”

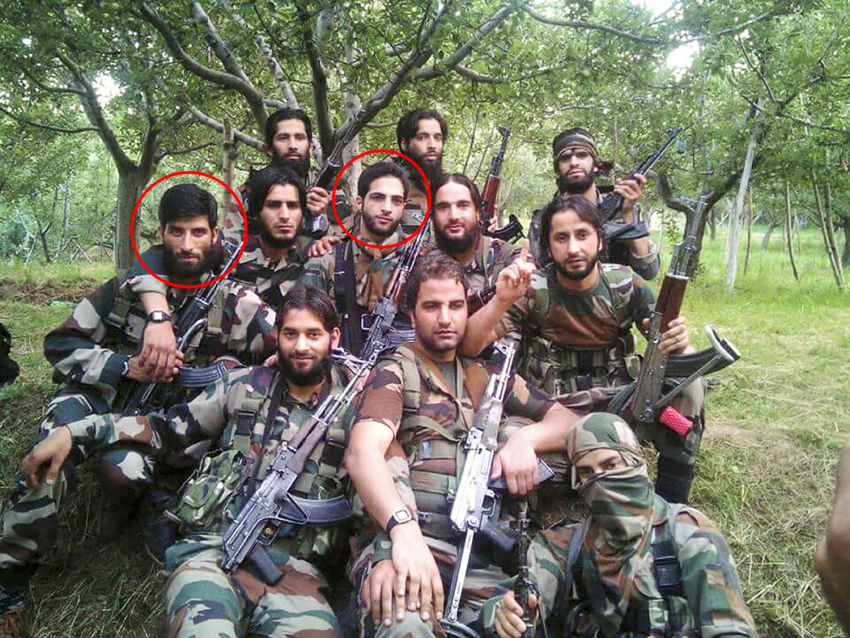

Pakistan funded and trained militants in Kashmir, it gave an almost parallel power to its non-state Islamist actors. Former president and retired General, Pervez Musharaf had admitted this to German magazine Der Spiegel. “They (underground militant groups to fight against India in Kashmir) were indeed formed,” he said.

Arif Jamal in his book Shadow War: The Untold Story of Jihad in Kashmir has revealed this in extensive details. He outlines the military adventure of President Musharraf, the infamous Kargil war, as a logical corollary to Pakistan’s policy of using jihadis as a strategic tool in the war against India. As Musharraf claimed it in his biography, it was waged to internationalise the Kashmir issue but it ended up isolating Pakistan internationally instead and for which Pakistan bore an enormous human cost. The financial cost of the war, met through Pakistani taxpayer’s money, excluding the compensation rose to $700 million. Jamal analyses how the role of jihadis was overstated by the military and the sacrifices of Northern Light Infantry (NLI) drawn from Gilgit Baltistan/Norther Areas were ignored by the media.

Arif Jamal outlined the formative phase of the Kashmir conflict and the evolution of the policy of using cross border Islamic militancy as an instrument of foreign policy, by focusing on Pakistan’s first jihad under direct military command. It led to partition of Kashmir into Pakistani and Indian occupied Kashmirs within a year of independence in 1947.

He discusses how CIA money, destined for the Afghan mujahideen in the 80s, was passed to Kashmiri jihadis under Zia, creating a vital nexus of power and patronage of Islamic militants by the Pakistani military. Jamat-i-Islami (JI), provided ideological strength and human resource, in addition to coordinating jihadi network with various brands of Islamic militants across the world, fuelling a more than twenty-five year insurgency.

Demystifying the notion of jihad as a selfless struggle for the glory of Islam, the author, exposed the vicious competitions among various militant organisations fighting for share in the spoils of holy war. With the ascent of secular mission of JKLF, the Kashmiri nationalist militants in the 80s, JI fought back to take a lead role in the Kashmir Jihad with the help of ISI in post-Zia period.

The book describes the factional struggle within the jihadi network and the hegemony of Hizbul Mujahideen and its allied organisations on the reign of terror that they unleashed in Indian-held Kashmir. They looted shops, bombed cinemas, targeted unveiled Muslim women and kidnapped, tortured and murdered Hindu businessmen and officials. In the process of conflict, Kashmiri society, which largely avoided communal riots at the time of partition, was convulsed into brutal violence, rising fundamentalism and communalism, and the flight of nearly the entire Hindu population from the Valley.

This decades-old narrative and strategy is not going to solve the Kashmir issue. Pakistan needs to abandon it’s habit of lionising militant groups and calling them ‘freedom fighters’ in the International Community that has justifiably grown hypersensitive or very paranoid about those groups, especially when the religiously motivated groups are endorsed. On the other hand, India, like international community, also fails to discern the real Kashmiri struggle on the face of militancy and turmoil.

Pakistan needs to understand that it has already lost the war on both moral and political grounds. Pakistan keeps lambasting Indian atrocity and crackdown over Kashmiri rebels, but at the same time stands on the opposite extreme. This fails to validate Pakistan’s claims of being an advocate of Human rights and a right to self-determination and ultimately fails to gain the wider popularity from Kashmiris and international community alike.

This policy undermines the Kashmir’s real political struggle and is the real reason why Kashmiris don’t see Pakistan as their saviour. Pakistan needs to construct a moral ground on which it can justify it’s claims, which unfortunately seems very unlikely in the current context of Pakistan’s foreign policy based on anti-India rhetoric.

Without the eradication of proxies motivated by ‘national interest’ of the two states, there can be no transparency and it would be foolish to expect a political solution.

Pakistan is not helping Kashmir, it is parroting it’s old moth-eaten case which it lost long ago and is repeating the same mistakes. What is worse than failure is perhaps not taking the lesson and there is nothing worse than that and Pakistan is going far beyond that.