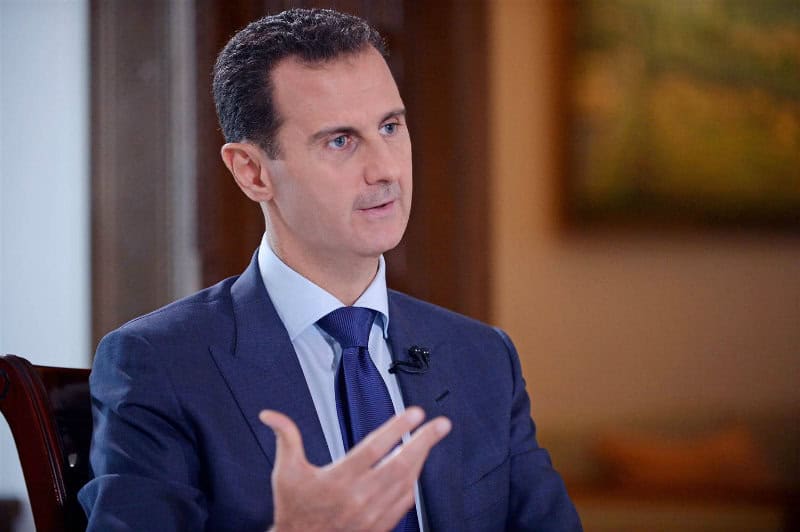

DAMASCUS – Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has declared that his government is ready to negotiate “on everything” during upcoming moot in Astana, Kazakhstan, indicating he is willing to consider the possibility of stepping down in free elections if rebels agree to restarting peace talks later this month.

Talks brokered by Syrian ally Russia and rebel supporting Turkey are supposed to take place in Kazakhstan before the end of January, but last week opposition groups said they had frozen the process in light of continued government strikes across the country.

Assad told French media in a recent interview that a Syrian government delegation is ready to leave for the Russian and Turkish-brokered negotiations in Astana, Kazakhstan, as soon as is necessary.

“We announced that our delegation to that conference is ready to go when they define… when they set the time of that conference. We are ready to negotiate everything, anything, it’s fully open, there’s no limit for those negotiations.”

He also highlighted that the problem with the upcoming Syria peace talks is whether “the real opposition” will be represented, Aljazeera reported.

There has been disagreement between the government and the rebels of the umbrella group known as the Free Syrian Army over whether certain factions in Wadi Barada – some with al-Qaeda or other extremist links – are part of the truce.

In comments made to French media published on Monday, President Assad said that the nationwide truce had been violated by rebels several times. He also defended the army’s push to recapture Wadi Barada, a rebel-held valley near Damascus where the main water supply to the capital has been turned off.

Assad said his forces were on the road to victory, citing the recapture of the city of Aleppo last month as a “tipping point” in the conflict.

“We don’t consider it (retaking Aleppo from the rebels) as a victory. The victory will be when you get rid of all the terrorists,” Assad said in the interview with France Info, LCP and RTL television.

“But it’s a tipping point in the course of the war and it is on the way to victory,” he said in excerpts provided by RTL.

During the interview, he also pointed out that there were still questions surrounding the talks including “who will be there from the other side”.

“We don’t know yet,” he added.

Turkey has suggested the Astana talks could be convened around the last week of January.

It was Assad’s first interview with French media since the December 22 recapture of the rebel-held east of Aleppo, which had been under siege for months.

Rebel forces, who seized eastern districts of the city in 2012, agreed to withdraw after a month-long army offensive that drove them from more than 90 percent of their former territory.

‘Assad stepping down’

When asked if he would be prepared to relinquish the presidency, should it become necessary, he replied: “My position is related to the constitution, and the constitution is very clear about the mechanism in which you can bring a president or get rid of a president. So, if they want to discuss this point, they have to discuss the constitution, and the constitution should be owned by the Syrian people, so you need a referendum,” the Syrian leader said.

“’If I feel that the Syrian people doesn’t want me [to be president], of course I wouldn’t be,” he concluded.

On apparent shifts in power recently, both across the Atlantic and in Europe, Assad chose to remain cautious. “We always hope that the next [US] administration [will] want to deal with the reality. [But] what we’ve learned in the last few years is that many officials would say something and do the opposite,” he said.

He added that the mainstream media had attempted to add fuel to the fire, although this had largely “failed in the West” and forced people to “look for the truth.”

“The truth was the main victim of the events in the Middle East, including Syria,” Assad added.

Nevertheless, he remained optimistic about the transition of power in the US – Donald Trump assuming White House.

“The Syrian problem is not isolated, it’s not only Syrian-Syrian; a major part of the Syrian conflict is regional and international. The simplest part that you can deal with is the Syrian-Syrian part, the regional and the international part depends mainly on the relations between the US and Russia.

“If there’s a genuine approach or initiative toward improving the relations between the United States and Russia, that will affect every problem in the world, including Syria. So yes, we think that’s positive,” Assad concluded.

Civil war

What began as a peaceful uprising against Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad five years ago became a full-scale civil war that has left more than 300,000 people dead, devastated the country and drawn in global powers.

Long before the conflict began, many Syrians complained about high unemployment, widespread corruption, a lack of political freedom and state repression under President Bashar al-Assad, who succeeded his father, Hafez, in 2000.

In March 2011, pro-democracy demonstrations inspired by the Arab Spring erupted in the southern city of Deraa. The government’s use of deadly force to crush the dissent soon triggered nationwide protests demanding the president’s resignation.

As the unrest spread, the crackdown intensified. Opposition supporters began to take up arms, first to defend themselves and later to expel security forces from their local areas. Assad vowed to crush “foreign-backed terrorism” and restore state control.

The violence rapidly escalated and the country descended into civil war as hundreds of rebel brigades were formed to battle government forces for control of the country.

The intervention of regional and world powers, including Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia and the United States escalated the situation, leading it to a full scale war. Their military, financial and political support for the government and opposition has contributed directly to the intensification and continuation of the fighting, and turned Syria into a proxy battleground.

Terrorist groups have also seized on the divisions, and their rise has added a further dimension to the war. Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, which was known as al-Nusra Front until it announced it was breaking off formal ties with al-Qaeda in July 2016, is part of a powerful rebel alliance that controls much of the north-western province of Idlib.

Meanwhile, so-called Islamic State (IS), which controls large swathes of northern and eastern Syria, is battling government forces, rebel brigades and Kurdish groups, as well as facing air strikes by Russia and a US-led multinational coalition

Thousands of militiamen from Iran, Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan and Yemen say they are fighting alongside the Syrian army to protect holy sites.

Russia, for whom President Assad’s survival is critical to maintaining its interests in Syria, launched an air campaign in September 2015 with the aim of stabilizing the government after a series of defeats. Moscow stressed that it would target only “terrorists”, but activists said its strikes mainly hit Western-backed rebel groups.

Six months later, having turned the tide of the war in his ally’s favor, President Vladimir Putin ordered the “main part” of Russia’s forces to withdraw, saying their mission had “on the whole” been accomplished. However, intense Russian air and missile strikes went on to play a major role in the government’s siege of rebel-held eastern Aleppo, which fell in December 2016.

The US, which blames President Assad for widespread atrocities and call for his ouster, has played a key and dangerous role by providing military assistance to “moderate” rebels, fearful that advanced weapons might end up in the hands of jihadists. Since September 2014, the US has conducted hundreds of air strikes on ISIS and government forces in Syria, backing the rebels fighting against Assad forces.

Saudi Arabia, which is seeking to counter the influence of its rival Iran, has been a major provider of military and financial assistance to the rebels.

Turkey is another staunch supporter of the rebels, but it has also sought to contain US-backed Kurdish Popular Protection Units (YPG) fighters who are battling IS in northern Syria, accusing the YPG of being an extension of the banned Turkish Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

In August 2016, Turkish troops backed a rebel offensive to drive IS militants out of one of the last remaining stretches of the Syrian side of the border not controlled by the Kurds.

Human toll

The UN says at least 250,000 people have been killed in the past five years. However, the world organization stopped updating its figures in August 2015. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a UK-based monitoring group, put the death toll at 310,000 in December 2016, while a think-tank estimated in February 2016 that the conflict had caused 470,000 deaths, either directly or indirectly.

More than 4.8 million people – most of them women and children – have fled Syria. Neighboring Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey have struggled to cope with one of the largest refugee exoduses in recent history.

About 10% of Syrian refugees have sought safety in Europe, sowing political divisions as countries argue over sharing the burden. A further 6.3 million people are internally displaced inside Syria.

The UN estimates it will need $3.4bn (£2.7bn) to help the 13.5 million people who will require some form of humanitarian assistance inside Syria in 2017. More than 7 million people are affected by food insecurity and 1.75 million children are out of school.