To view history as a factual constraint is, apparently, optional in the current landscape of South Asian politics. New Delhi’s recent suggestion that Sindh is merely a temporary absentee from a unified Indian consciousness represents a bold, albeit factually hollow, rewriting of the past. Assertions by senior leadership that Sindh was “always ours” amount to more than nostalgic pining; they represent a calculated assault on the legitimacy of partition’s legal framework. By ignoring the statutory reality of Sindh’s accession, these narratives attempt to replace the democratic verdict of 1947 with a version of history that exists only in the imagination of the political right.

To dissect this narrative with the factual clarity it demands, one must first look to the legal bedrock of 1947. The assertion that Sindh was “snatched” or is naturally part of the Indian Union ignores the defining event of Partition: the democratic will of the governed. In June 1947, the Sindh Legislative Assembly became the first provincial legislature on the subcontinent to pass a resolution explicitly opting for Pakistan. This was not a decision made under the duress of a conquering army or the pen of a distant cartographer; it was a sovereign legislative act by the elected representatives of the Sindhi people, later ratified by the British Parliament via the Indian Independence Act. To delegitimize this vote is to unravel the entire legal fabric of the post-colonial world. Sindh did not “fall” to Pakistan; it chose to create it.

Furthermore, the modern Indian political imagination often suffers from a conflation of geography and statehood. The narrative suggests a yearning in Sindh for a Delhi-centric union, yet the province’s political trajectory in the 20th century was defined by the exact opposite impulse. The historical record belies the notion of an innate desire for union. Well before partition, the primary vector of Sindhi politics was the dissolution of its link to the Bombay Presidency—a move explicitly championed in Jinnah’s constitutional demands of 1929. This insistence on administrative decoupling was driven by an acute necessity to insulate a unique Muslim demography from external dilution. When Sindh finally wrested its provincial autonomy from the colonial administration in 1936, it was signaling a departure from the subcontinental mainstream, setting the stage for its natural alignment with the embryonic state of Pakistan.

To paint Sindh in the monochrome shades of a unified Indian past is to strip the region of its true soul. Such claims conveniently sidestep the defining transformation of the region: its status as Bab-ul-Islam. Since the eighth century, the soil of Sindh has cultivated a worldview defined not by the Vedics, but by the egalitarian ethos of Islamic mysticism. This is a culture that has evolved over a duration far exceeding the lifespan of modern nation-states. The syncretic warmth of the local shrines often confuses outside observers; yet, this openness is rooted in the security of a deeply entrenched Muslim political consciousness—one that chose a separate destiny for a reason.

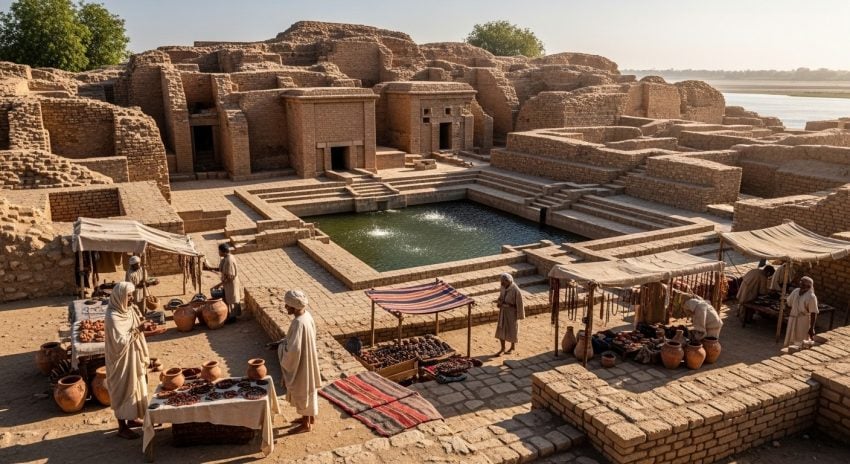

Even when the aperture of history is widened to antiquity, the claim of a primordial, unified “Hindu Rashtra” encompassing Sindh dissolves under scrutiny. The “India” that Rajnath Singh governs is a modern nation-state established in 1947. Even when one examines antiquity, the narrative of a perennial ‘Hindu Rashtra’ encompassing Sindh is historically unrecognizable. The map of the ancient subcontinent was not a static deed of ownership, but a dynamic patchwork of competing kingdoms. The grand consolidation under the Mauryas was an anomaly, not the standard, and it was helmed by Ashoka—a patron of the Buddhist path who stood in philosophical opposition to the caste-based order championed by today’s Hindutva movement. The irony deepens when considering the Indus Valley Civilization. These urban pioneers, the region’s indigenous ancestors, existed worlds apart from the pastoral Vedic traditions that migrated from Central Asia. To retrofit the ruins of Mohenjo-Daro into a modern Vedic narrative is a fundamental anthropological error.

Ultimately, the argument exposes the dangers of romanticizing geography. The “sanctity” of the Indus River flows through the terrain of reality, not the maps of political wishful thinking. If rivers determined borders, the Ganges and Brahmaputra would demand a redrawing of half the Asian continent. The political destiny of Sindh was settled not by the flow of water, but by the flow of votes and the collective will of a people who envisioned a future within Pakistan.

Declarations to the contrary may possess a fleeting utility for fueling campaign narratives across the border, but they carry no currency in the long view of history. The status of Sindh is not a question mark; it is a resolved reality. It stands secure and sovereign, anchored by the deliberate, democratic verdict of 1947—a foundational decision made by the people themselves, which no amount of rhetorical nostalgia can retroactively erase.